Tools

Of speech and language therapy

Ancient innovations

Speech and language therapy gets its tools from a wide variety of fields. I believe that the first and last of these tools is linguistics, rather than bells, whistles, and suchlike, as sometimes marketed to parents.

Three of the pioneers in speech and language pathology were the Reverend William Holder, John Thelwall, and Alexander Melville Bell, working over the period from the 1660s to the late 1900s, starting long before the term, linguistics, came into use. More recently there is the theoretical and empirical research pioneered by Noam Chomsky in the 1950s and now developed by a huge worldwide community of scholarship working in almost all fields of linguistics, now dominant in many of these fields, but not in clinical linguistics, as commonly understood.

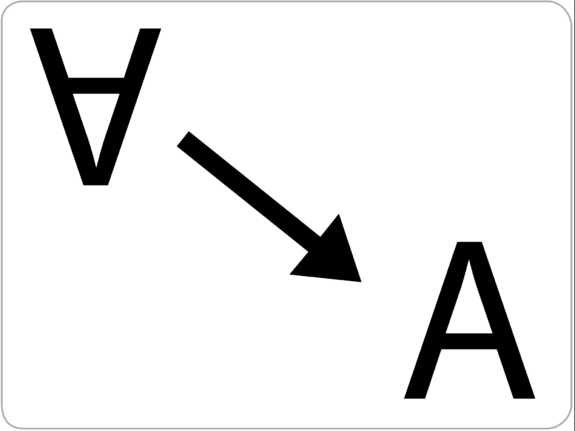

It is important to recognise that Chomsky’s tradition of linguistics started long BEFORE what is sometimes characterised as the ‘constructivist’ tradition represented by William Croft (2002, 2004, 2010), Ben Ambridge (2004, 2010) and others . Efforts to represent Chomsky’s tradition as some sort of interloper seem to me just historically wrong. The history is the other way round.

Knowing only of Chomsky’s work, not knowing any of that of any of the pioneers, as I characterise them here, in 1983 I developed the same notion of giving children ‘pretend words’ to say in a highly structured sequence, but with the natural stress contours of English, as described here under the heading of Possible words.

The therapy aspect here has recently been misrepresented by what seem to me like some very unfortunate shenanigans.

Going back long before the work of the pioneers of speech and language pathology, and other modern areas of study including anthropology, psychology, sociology, there have been significant explorations and investigations in linguistics, from the invention of what quickly became the modern alphabet, about 3,200 years ago in the Middle East, continuing in India and ancient Greece.

The International Phonetic Alphabet

In the late 19th century, scholars from France, Germany and England got together to devise what became the supposedly International Phonetic Alphabet or IPA (not really international with different styles in Europe and Norh America). All native speakers of prestigious varieties of their respective languages, the original proponents of the IPA decided to base it on points of commonality like p, b, t, d, m, n. They thus turned their backs on the more radical ‘Visible Speech’ developed 30 years earlier by the Scot, Alexander Melville Bell. In the aftermath of war with Russia, Bell’s original motivation was international peace. 30 years later, war was looming again. Russia had recently taken control of the Caucasus, and was mainly concerned to defend that. Britain, Belgium, France and Germany, all had colonies in Africa. Britain had the largest share. The other powers all wanted to enlarge their respective shares. The only uncertainty was who would side with who, including Russia. The founders of the IPA were very aware of these political undercurrents, all wanting their own language to become the IPA standard. In the end they settled on a compromise. The English variety which the IPA inventors assumed as a standard of English was what later came to be known in Britain as ‘Received Pronunciation’ or RP.

So the term, phonetics, is often used to define an alphabet, designed by those scholars primarily to represent the sounds of their respective language. It was only later that the system was developed to represent the sounds of all the world’s languages.

IPA is obviously very useful in speech and language therapy for representing children’s speech and disordered speech in a clear and systematic way, especially for a language like English with a large number of vowels, a lot more than the Latin or Greek for which our alphabet was originally designed.

To characterise a segment as a sound or phoneme from some particular variety of, say, English, it is conventionally shown in slashes. To characterise a segment as it is implemented in the speech of an individual, it is conventionally shown in square brackets.

But for the sake of accessibility, I don’t use phonetics here. I just use capital letters in an ad hoc way. I just hope it is understandable.

Seven short vowels

By the profound discoveries of two of the world’s first practitioner / linguists, by William Holder, that a vowel system can be organised into a line around the bottom and sides of the orange shape in the diagram for one of the vowel systems of English on the International Phonetic Alphabet page, and by Alexander Melville Bell, that the line is not straight, but narrower at the bottom than at the top. Neither of them knew that the series here is defined by a continuous change in the value of the ‘formants’ or the main concentrations of acoustic energy in the vocal tract. This idea would not be clearly described until the end of Bell’s life. It would not be applied to speech until 1960, 55 years after Bell’s death. So Bell could not tell that this shape should be drawn as a rhombus with four edges rather than as a triangle.

It was only in the 1950s tht it became possible with movies and X-ray to trace the position of the tongue as a speech sound was articulated. So it was not originally realised that there are really two shapes, a rhomboid connecting the vowels in the diagram above and a larger, more U-like, shape connecting the long vowels in Southern British English, he, air, arm, or, and who, implemented with more muscular tension, and closer to the edges of what is known as the ‘vowel space’. But the discoveries of Holder and Bell were still profound. They demonstrate the scientific value of careful clinical observation.

Imperfections

The lines of the rhombus are idealisations. The real line wiggles. And the wiggles vary from speaker to speaker. Daniel Jones proposed a system of perfect idealisations which he called the ‘cardinal vowels’, taking the notion of cardinality directly from Bell, but without accreditation. Listeners clearly idealise what they hear. But the application of this is not obvious.

I have never been able to see any clinical utility in the notion of cardinal vowels. Jones himself showed little or no interest in the issue of speech pathology. I don’t know if the cardinal vowels idea has ever been applied to speech pathology, As far as I know, it hasn’t.

Divergencies

Unfortunately, despite the name, the IPA is not always used consistently. The long vowels are sometimes written by a character followed by a comma, sometimes by the character followed by an h, and sometimes by the character on its own – for instance with the vowel in he as /i/ or /i:/ or /ih/.

The affricates in chew and jew are sometimes shown as two segments, representing the stop onglide and the fricative offglide, and sometimes by a single character with a diacritic, representing the singularity of the phonemes.

And the single fricatives in show and azure are also shown in two ways, one by a single character to emphasise the specificity and sometimes by /s/ and /z/ with a diacritic to emphasise the minimal, one feature, difference. The feature in question can be analysed in different ways:

- By how close the point of greatest narrowing is to the front of the mouth;

- By whether or not the gesture is by the tip or apex of the tongue;

- By whether or not there is a characteristic grooving.

Different speakers get the same sound in different ways according to the shapes of their mouths and the spacing of their teeth.

The devil is in the detail

Phoneticians or phoneticists often believe that phonologists gloss over the important details of individual sounds or phonemes.

A case outside the scope of the IPA

By the discovery of William Labov (1994) and (2001) there are what are known as ‘chain vowel shifts’ happening in North America right now which very much like what Otto Jerspersen called the ‘Great English vowel shift’ which happened in England between the times of Geoffrey Chaucer and William Shakespeare with the long vowels rising in the vowel space and becoming diphthongs as they reached the top of the space. What Labov discovered is that at least in North America there seem to be four stages, an initial stage, and end stage, and two in-between stages. The problem from an IPA perspective is that the in-between stages can only be shown by diacritics. This does not well capture the essential linearity of the process.

It might seem that what is happening here is that any point in the process, the height of a vowel is just at some arbitrary position on a gradient. The problem with this is that it implies that the acquisition process is essentially in two parts, one in fixing a set of approximate categories, and the other in attaching exact values to them. This doubles the overall scale of acquisition. It seems to me enormously preferable to reconfigure the task to avoid any appeal to gradience. One way of doing this, as suggested by the proposal here, is to follow the analysis of Diana Archangeli (1984) by which phonemes are ‘built’ in steps, feature by feature. The effect of gradience is an artifact of minor changes in the ordering of the building.