Framework

Two hidden dimensions

By the framework assumed here, language is organised in three dimensions. One dimension is obvious in the fact sentences vary in length. But two dimensions are hidden – by virtue of being DERIVED.

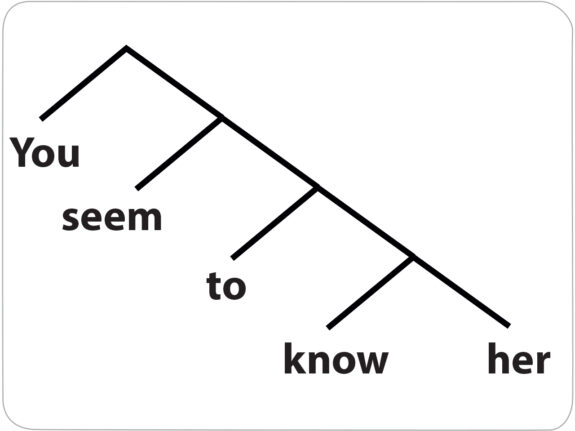

Two of these hidden dimensions are captured by the branchedness in the diagram above. By the framework here, this is conventionally shown by a series of forks or what is now commonly known as a ‘spine’. Essentially, this is a ‘decision tree’, starting at the bottom. The forking can continue, as by the diagram above, in fact indefinitely. This extraordinarily simple device makes language infinitely creative, using only one simple procedure or operation. Consider these:

She’s doing well.

The girl in the corner is doing well.

The dark-haired girl in the corner is doing well.

The dark-haired girl in the corner is doing incredibly well.

We think the dark-haired girl in the corner is doing incredibly well.

You know we think the dark-haired girl in the corner is doing incredibly well.

I suspect you know we think the dark-haired girl in the corner mistakenly believes that she is doing incredibly well.

We can go on multiplying the variations in all of their dimensions any number of times. There is no point at which this ceases to be English. And not just English, but any one of the other six or seven thousand or so languages spoken around the world. All human languages have this infinite creative potential.

By the framework here, this has to have been the very first step in the evolution of speech and language. It might seem logically posssible for speech and language to have evolved from a simple function puttong one word before another. But as Marinus Huybreghts (2019) shows very elegantly, a system with an infinite output cannot grow from one with only a finite output. This leaves a tree structure as the only possible starting point.

Immediately below I show only the first and second forks.

Why make things complicated or more complicated than necessary? Actually this is not more complicated than necessary. A branched diagram is less complicated than any alternative. Consider the child with 100 words who says things like “Get down” and “Pick up” and nothing longer or more complicated– in a way typical of early language, as at one and a half. Let us set aside the fact the opposite orders are not heard. The same child does not say either “Down get” or “Up pick”. It might be said: Of course, the child doesn’t. He or she has never heard anything like that. Such structures are not part of English. But if the child’s grammar is capable of generating two words in one order, it is capable in principle of generating the same two words in the opposite order. That would yield a total logically possible output of 10,000 two word combinations or strings. But even pushing things to that absurd limit, the total logically possible out put is still finite. This would be equivalent to using the ‘successsor function’ as used in counting the positive integers from one to two to three, and so on. But the successor function is limited because it reveals nothing about the relations between the ‘leaves’, as these are known in maths and computer science. The child with just two words would commonly be described, quite correctly by the framework here, as ‘just starting to talk’. Such a child is on a pathway. And that pathway ends with the capacity of Shakespeare and Macbeth to output an infinite set of structures. Crucially, these structures are not in some random order, as they would be by just squaring the words in the lexicon, with get, down, pick, up, in any combination of two in either order, or by just raising the exponent for longer strings like “Want get down”. The reason for the tree diagrams above is that the structures contain elements that are inside one another, if they are considered as a linear string. Consider “Did you do the washing up?” and “You did not do the washing up.” Did and do are formed from the same do root used in different ways in English. But in both cases do is pronounced in between did and washing up. And you in the first case and not in the other are prononnced in between did and do in what is clearly a verbal element. Now these complex orderings could be described as different positions on different sorts of string. But it would be vastly more complex than a tree structure with the positions of the elements varying one at a time, as by the disagram above of “You seem to know her”.

In 2019, Marinus Huybrechts distils with great simplicity and clarity a line of reasoning by which a function with an infinite output just can’t grow out of a system with a finite output. If this line of reasoning is correct, as I believe it is, what the small child is doing by his or her first word is rather m0re sophisticated than it might appear to be. This is not just a matter of relabeling old insights, as by some marketing operation, but a correct understanding. Human speech and language development has to START with a potentially infinite output. To say that this is not intuitively obvious is perhaps something of an understatement. Whatever system underlies the child’s ability to utter his or her first word does not seem to be anything like a system with an infinite potential. Taking the Huybrechts conclusion to the limit, even the first word opens to door to an infinite output system.By Huybrechts’ result, there is no way of characterising one pathway from the two words in “get down” to the five words in “You seem to know her” other than by postulating a potential branchedness in the simplest structures.

But in an effort to make it clear that there are in fact two hidden dimensions in this framework, on this topic I use a novel notation of chains for links, the ‘merging’, to use Noam Chomsky’s terminology since 1995 (or what I call by the proposal here the ‘decomposing and recomposing’) of one element with another, and springs for projections. Together the links and springs work together to apply ‘recursively’ – over and over again. These two hidden dimensions are not a figure of speech, but a representation of the underlying maths of the cognitive process here.

Because we experience language as a sequence of words, we think of sentences in terms of their length. So one dimension is from left to right. And “You seem to know her” is longer than “You know her”, with a relation between you and seem which cannot be captured (in English) other than by this ordering. But a second dimension is from bottom to top, allowing Shakespeare to set out Macbeth’s deluded thoughts. And a third dimension is from left to right as a consequence of the way that this structure is expressed for the sake of human perception, which is essentially linear, irrespective of whether the structure is heard in speech or seen in sign language. By the framework here, the length is an artifact of the derivational depth, rather than the other way round.

Universal Grammar – UG

By this framework, often characterised as ‘generative’, there is something which is reasonably referred to as ‘Universal Grammar’ or UG. This does not propose (absurdly) that there is just one language. This proposes just that there are deep and very significant commonalities across all languages, and that the commonalities are at least as important as the obvious differences. As Roger Bacon put it in the 13th century, “In its substance, grammar is one and the same in all languages, even if it accidentally varies.”

The notion of UG is supported by a great deal of evidence. There are some who strenuously deny that there is any such thing. But it seems to me that if there is no such thing as UG, the notion of language disorder is ultimately not definable, and that therefore there can be no well-grounded scientific investigation of the condition or well-motivated treatment for it.

By the evidence of the proposal here, speech and language evolved and develop in children today by a continuous series of highly-specific steps. What is commonly referred to as ‘Universal Grammar’ or UG is reflected by a series of commonalities across diverse languages. One of these is the contrast between words used as nouns like horror, as adjectives like horrible, as verbs like horrify, and elements known as ‘functors’ whose only role is in relation to one or more other parts of the structure like the in ‘the horror’ and that in “I think that he’s horrible”. All languages divide their words into these two main categories, functors on the one hand and what are traditionally known as ‘parts of speech’ or what are known as ‘lexical items’ in the framework here, on the other.

In 1965 Chomsky proposed that UG was specified by the human genome. For some reason I don’t understand, this idea has been steadfastly resisted or ridiculed ever since by many who have no problem with other seemingly innate human-specific capacities like our ability to carry out mathematical operations, or the implications of Florence Goodenough’s 1926 ‘Draw a man test’ (still widely used) interpreting two dots for eyes, a vertical line for a nose, a horizontal line for a mouth, and an enclosing circle for a head.

But if there is anything like a genetic UG, it is not just possible, but likely, that this natural endowment varies slightly across individual members of the species. At least some aspects of these variations surface as speech and language disorders of varying degrees of severity, most resolving spontaneously in the course of childhood, but some persisting throughout life as some sort of communication problem.

In relation to UG, there are many discernible positions. By the simplest position, first proposed by Chomsky (1995), there is a single overarching functionality which he calls ‘Merge’, by which the whole of grammatical structure is built from one cyclical process of merging two elements and characterising one as the defining property of the Merge. On the most complex account, proposed by Stephen Pinker in 1994, there is an extremely rich ‘Language Instinct’, as he proposes in his book by that name. On a simpler account, proposed by Ray Jackendoff (2002) now endorsed by Pinker, there is a network of 13 functionalites which the learner has to traverse in order to reach full competence. By another model, due to Naama Friedmann, Adriana Belletti and Luigi Rizzi (2021), there are just three key functionalies. By the proposal here, there are eight steps, all defined in a single format, reflecting the broad shape of the original evolutionary process.

The hidden steps

In the spoken word know, the N sound precedes the OH sound, and in the expression “You know”, you comes before know, and the sentence “You seem to know her” has five words from left to right. The obvious horizontal dimension reflects the sequentiality of speech. Sign is more complex in as much as it allows the two hands and head and eyes to do more things at once. But there is still inescapable sequence as a necessary consequence of the way human articulation, perception, and memory are organised. But largely by the work of Noam Chomsky, there are two hidden dimensions in “You seem to know her”. By one hidden dimension, You, as the first word, has a clear relation with know, as the fourth. This links the two clauses, the first with seem, as its verb, the second with know. The link is by an unspoken label, implicit in the linkage, shown here as a chain. By the other hidden dimension, the ‘know her’ clause, traditionally described as ‘subordinate’, is generated as the first step in a DERIVATION. By these two hidden dimensions, the depth of the structure is an event.

In “You seem to know her” the two words, know and her, differ on the point that her picks out some individual female known to the speaker and listener, or previously identified, and know plainly does not refer in any sense at all.

By the first step in the derivation, they are strongly linked together.

It is the verb, know, which constitutes the ‘head’ of the resulting expression, and PROJECTS. The projection is shown here by a spring to denote the specific direction.

So the immediate effect of the linkage is to form the ‘verb phrase’ know her, while preserving the history of how it was formed, shown here by the red stripe. The phrase is quite distinct from its two constituents. The distinctness is captured by the nature of the event and the verticality. The dimensionality could be captured in various ways. But verticality is widely used.

A later step introduces the subject, you, forming the bare bones of a sentence and a meaningful proposition, either true or untrue, still preserving the history so far, shown here by the two stripes, red and blue.

The need for the vertical dimension is shown by the step of introducing the word seem which calls into question the certainty of the knowing, by a previous step in the derivation.

Or, conventionally, by a branchedness diagram (simplified somewhat here):

By further steps of projection, not shown here, you is copied from its original position by the green block to a higher position by a further grammatical event commonly known as ‘raising’. And know is raised in the structure to be pronounced with to, as by “You seem to know”. And for the purposes of pronunciation, you is ignored in the position where it originated, although it remains there for the sake of understanding.

The direction of thought

It is sometimes thought that the main focus in the analysis of child speech should be on what children most often get wrong. But that does not answer the questions: Why do children get wrong what they do, not just individually, but generally? And how do they end up talking ‘correctly’, understanding one another, and agreeing about meanings? To find an answer, I propose to consider what learners HAVE to attend to.

One example of this necessary learning is the very complex phenomenon known as ‘ellipsis’ – or not pronouncing key elements of structure, as in “She said something interesting, but I forget what”. This can be said as “She said something interesting, but I forget what she said”. But the second instance of ‘she said’ is reliably understood, even though it goes commonly unpronounced. Obviously, this sort of structure is not part of early child language. But the language learner must be on a pathway such that this sort of structure becomes learnable in due course. He or she must be attending to the interplay between what is pronounced and what is not pronounced. Only in this way can the child become a competent native speaker of his or her target language. The learning process begins with simple questions like “Where are your socks?” with the possible answer, “There”, not pronouncing “My socks are…”

The two considerations of what the language learner must be attending to and what must have happened in the evolution of speech and language are what justify and motivate the research program and the proposal here.