The International Phonetics Alphabet

The IPA and the phonetics of English

The great utility

The term, phonetics, is often used to define an alphabet, designed to represent the sounds of any language, as recognised by native speakers.

IPA is obviously very useful for representing children’s speech and disordered speech in a clear and systematic way, especially for a language like English with a large number of vowels, a lot more than Latin or Greek for which our alphabet was originally designed.

To characterise a segment as phoneme from some particular variety of say English, it is conventionally shown in slashes, for instance as /i/ or /i:/ or /ih/ to represent the vowel in he. To characterise a segment as it is implemented in the speech of an individual, it is conventionally shown in square brackets.

But I don’t use phonetics here for the sake of accessibility.

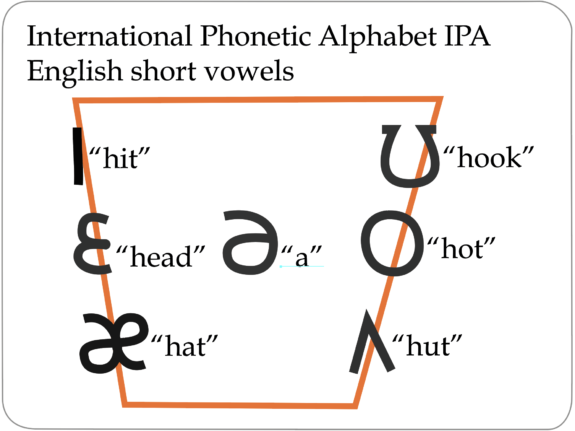

Seven short vowels

By the profound discoveries of two of the world’s first practitioner / linguists, by William Holder, that a vowel system can be organised into a line around the bottom and sides of my orange shape in the diagram above, and by Alexander Melville Bell, that the line is not straight, but narrower at the bottom than at the top. Neither of them knew that the series here is defined by a continuous change in the value of the ‘formants’ or the main concentrations of acoustic energy in the vocal tract. This idea would not be clearly described until the end of Bell’s life. It would not be applied to speech until 1960, 55 years after Bell’s death. So Bell could not tell that this shape should be drawn as a rhombus with four edges rather than as a triangle.

It was only in the 1950s tht it became possible with movies and X-ray to trace the position of the tongue as a speech sound was articulated. So it was not originally realised that there are really two shapes, a rhomboid connecting the vowels in the diagram above and a larger, more U-like, shape connecting the long vowels in Southern British English, he, air, arm, or, and who, implemented with more muscular tension, and closer to the edges of what is known as the ‘vowel space’. But the discoveries of Holder and Bell were still profound. They demonstrate the scientific value of careful clinical observation.

Imperfections

The lines of the rhombus are idealisations. The real line wiggles. And the wiggles vary from speaker to speaker. Daniel Jones proposed a system of perfect idealisations which he called the ‘cardinal vowels’, taking the notion of cardinality directly from Bell, but without accreditation. Listeners clearly idealise what they hear. But the application of this is not obvious.

I have never been able to see any clinical utility in the notion of cardinal vowels. Jones himself showed little or no interest in the issue of speech pathology. I don’t know if the cardinal vowels idea has ever been applied to speech pathology, As far as I know, it hasn’t.

Divergencies

Unfortunately, despite the name, the IPA is not always used consistently. The long vowels are sometimes written by a character followed by a comma, sometimes by the character followed by an h, and sometimes by the character on its own.

The affricates in chew and jew are sometimes shown as two segments, representing the stop onglide and the fricative offglide, and sometimes by a single character with a diacritic, representing the singularity of the phonemes.

And the single fricatives in show and azure are also shown in two ways, one by a single character to emphasise the specificity and sometimes by /s/ and /z/ with a diacritic to emphasise the minimal, one feature, difference.

The devil is in the detail

Phoneticians or phoneticists often believe that phonologists gloss over the important details of individual sounds or phonemes.

A case outside the scope of the IPA

By the discovery of William Labov (1994) and (2001) there are what are known as ‘chain vowel shifts’ happening in North America right now which very much like what Otto Jerspersen called the ‘Great English vowel shift’ which happened in England between the times of Geoffrey Chaucer and William Shakespeare with the long vowels rising in the vowel space and becoming diphthongs as they reached the top of the space. What Labov discovered is that at least in North America there seem to be four stages, an initial stage, and end stage, and two in-between stages. The problem from an IPA perspective is that the in-between stages can only be shown by diacritics. This does not well capture the essential linearity of the process.

It might seem that what is happening here is that any point in the process, the height of a vowel is just at some arbitrary position on a gradient. The problem with this is that it implies that the acquisition process is essentially in two parts, one in fixing a set of approximate categories, and the other in attaching exact values to them. This doubles the overall scale of acquisition. It seems to me enormously preferable to reconfigure the task to avoid any appeal to gradience. One way of doing this, as suggested by the proposal here, is to follow the analysis of Diana Archangeli (1984) by which phonemes are ‘built’ in steps, feature by feature. The effect of gradience is an artifact of minor changes in the ordering of the building.