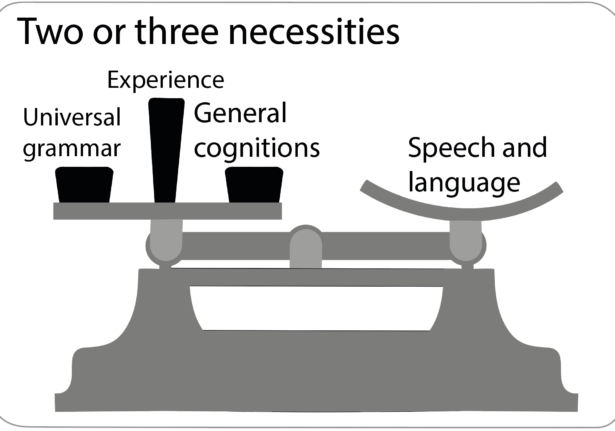

Two or three necessities

Without which there could not be speech and language

One obvious necessity is the experience of hearing people talking, the primary linguistic input, as this is called. But this experience alone is not enough. There are also the properties in language which have led to the postulation of a ‘Universal Grammar‘, or UG, as a species-specific, species-universal character of humans, and a whole gamut of cognitions from epistemic notions of certainty, posssiblity, probability, doubt, to moral imperatives. There is a real uncertainty about the relative weightings between these three sets of factors. One sort of evidence here is from what seem like a number of anomalies in language, many not identified until the 1960s.

The anomalies take various forms:

- Where the meaning of what might seem to be a free variable is arbitrarily restricted – in the case of pronouns like he in “He bought some flour, before Daddy made the bread” where he can’t be Daddy. when in “Before he made the bread, Daddy bought some flour” there is no such restriction;

- Where s functor is blocked or not pronounced – in the case of that in “Who do you think that died” ungrammatical to most English speakers in contrast to “Who do you think died?” with the blockage undone in “Who do you think that he was killed by?” ;

- Where, conversely, a functor has to be pronounced –in the case of that in “That he is a fool is obvious”;

- Where a functor is freely pronounced or not pronounced – in “It is obvious that he is a fool” or “It is obvious he is a fool” – where there might be a difference in meaning, when in fact there is no difference in English;

- Islands, where what might seem to be a free variable leads to an uninterpretability, as in “What did you forget who had put in the oven” when “What did you forget we had put in the oven” seems fine. The island is a point in a structure from which escape is doubtful, questionable or problematic.

- Elipsis, where particular sorts of structure are unpronounced, in some cases with the grammar of what is pronounced sometimes changed, as in “Teddy was naughty, not me”, where the ellipsis involves “I was not naughty”, with the case of the subject and the order with not both changed.

While the details of these anomalies are often language-specific, with differences between very closely related languages like English and Dutch, all six of these phenomena seem to be language universal.

There are two obvious questions about these apparent anomalies: How do children learn about them without being taught or having them explained? And how is it that there is broad agreement on these points between native speakers despite wide variations of culture and levels of education? Some children have many hours of careful, diligent instruction about their grammar. Other children have none whatsoever. There are other similar, seemingly anomalous phenomena in numerous other languages, closely related to English like German, Dutch and Danish, or clearly unrelated to English like Hebrew and Arabic. The simplest and most obvious explanation of phenomena common to across a wide sample of related and unrelated languages is by UG. Children are somehow guided towards an appropriate analyis of what they hear said by their biological inheritance, in the same way that they inherit a body with two legs and two arms, with one bone in each of the parts closest to the body, two bones in the further part, and five fingers and toes. Children were not born knowing how to talk, but knowing how to interpret the evidence of what they heard, their linguistic experience. But this does not explain the differences beween languages. The big problem with any sort of UG account of the anomalies is the complexity of the data. While there are similar anomalies in most, if not all, languages, there are large or small differences in how they apply from one language to the next, and sometimes, as noted above, from one speaker of what is seemingly the same dialect to the next. A UG account of such variability is quite implausibly complex. If the explanation is as complex as what is being described, there is no explanation.

An inheritance with respect to the anomalous behaviour of pronouns would be useless without a rich experience of grammatical structure and what are known as their ‘antecedents’, in the case of the examples above, Daddy, or what might be Mummy, or anyone else capable of buying flour, bread, or anything else.

By a recently developed account, anomalies in phenomena which are seemingly specific to language like ellipsis, islands and the understanding of pronouns, should be explained as far as possible in terms of the categories of general cognition. Noam Chomsky often refers to these as ‘third factor’ cognitions, where the first and second factors are experience and UG. Among these third factor cognitions, two of the most obvious are the notions of an entity and an event. The idea here is not new. It corresponds very loosely to the notion in many traditional grammar books for children of nouns as names of people, places and things, and of verbs as doing words. Without the notion of an entity, reference would seem to be impossible. And without the notion of an event it would seem hard to conceive of a verb or any sort of time scale as expressed by the -ED in talked or the difference between grow and grew. Similarly, without the notion of what is known as the ‘Theory of Mind ‘or TOM, or understanding that others can think about thoughts just as we can, it impossible to make sense of thinking, knowing, or saying anything in particular. The problem with third factor cognitions is that they are hard to define because they are even more difficult to test experimentally. Mike Tomasello has shown experimentally that at least some chimpanzees have at least some version of a TOM. But very few of those most familiar with non-human primates have anything resembling a modern human cognition. As far as I know, only once has a non-human ever been cited as a co-author. While it seems obvious that third factor cognitions necessarily underly much of grammar, the relative weightings of them and UG are highly uncertain. Both and the relation between them are the topic of intense ongoing debate.

From an evolutionary perspective, it is hard to see how any of the seven evolutionary steps by the proposal here could have got off the ground genetically without a degree of more general cognitive infrastructure. For instance, it is hard to see how the first combination of a primordial prototype noun and some contrasting element could have occurred without some foundational cognition. But whatever the relative weightings of UG and general cognition, at least some aspects of general cognition and all aspects of UG seem to be necessarily part of the human genome, and clearly not part of the genome of any other known species.