Why linguistics?

What no other species has

Speech and language are rather obviously complex. The faculty and its universality make human beings special. There are other special talents which humans have. But the learning of speech and language starts earlier and proceeds to a common conclusion more completely and reliably than the learning of any of any other faculty. No other species communicates with anything like the compositionality of human language. The generality and exclusivity are rather obvious. But speech and language are developmentally vulnerable – the topic of the commonest sort of developmental issue. How is it that the learning process is both reliable and vulnerable? There seems to be a contradiction.

Imagine the claim on a set of instructions for some complicated gadget: It always works perfectly, except when it doesn’t. Obviously absurd. How is the absurdity to be avoided?

The science

The science of speech and language is known as linguistics. Along with astronomy, linguistics is one of the two oldest sciences.

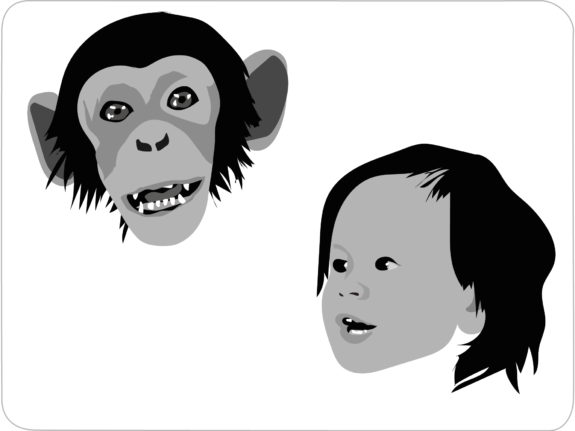

It is often noted that humans differ from chimpanzees by less than 2% of their DNA. But within that small percentage, one singular difference is human speech and language. With varying degrees of success, baby chimpanzees have been taught some signs from sign and artificial languages. But baby chimpanzee sign language is not like human baby sign language. It does not have the characteristic structure of human language, with both an infinite capacity and a commonality across all members of the species. On the infinity, sentences can be lengthened indefinitely, as by “What are you saying?” “I know what you’re saying”, “They think that I know what you’re saying”, “She suspects that they think that I know what you’re saying”, and so on. And there is commonality in the fact that this is reliably understandable. The understandability declines as the length and complexity increases. But there is no point at which the structure ceases to be English, as just one arbitrarily selected human language. No non-human has ever shown any awareness of the little word that in structures like “They think that I know what you’re saying”. In some languages, English being one, it is not pronounced in “They think I know”, but pronounced in “They think that I know ”. In English, that is optional. But the fact that it is specified by the grammar, whether pronounced or not, opens up both the infinity and the commonality. The device or devices which allow language to have these capacities is known as syntax.

By the age of three children are growing their lexicons by 10 or so new words every waking hour, more in a week than any non-human in a life time, and not just asking and understanding questions, but saying things like “I want to stand on the chair to see what’s happening”, with three bits of sentences embedded inside one another, with I understood as the subject of three of the verbs, but pronounced as the subject of just the outermost verb in the structure. I is is displaced twice, as the underlying subject ot see and of stand, One of the subjects of the research here said this just before he was three. The other subject said something similar at the same age. To explain this on the basis of a simple stringing together would be more complex than by repeating the same sorts of structure and then assembling them into one larger structure of the same fundamental sort.

The most profound clinically relevant lesson from linguistics is that there is such a thing as the learnability space. Some aspects of speech and language fall within it, and have to be learnt during every normal childhood. There are two interlinked aspects of what has to be learnt.

By one, the grammar has to specify all and only those phenomena that contribute to the faculty of language. The grammar has to do so in such a way that it is finitely learnable, and, by recent formulations, in such a way that it could plausibly have evolved. By this finite learnability, the learner learns that the order of adjectives, like good or bad, and what they modify varies according to whether it is a pronoun, like something, nothing, anything or everything which gets modified, or a noun, like song, idea, government. And this learning is robustly expected. A speaker saying “I see bad nothing” or “I like books good” would be barely understood, if at all.

By the second, the grammar has to be broken down into the smallest possible chunks. Such a grammar is both reductionist and ‘generative’ in the sense that it generates structures freely in two directions, by the speaker creating meaningful forms and by the listener assigning analyses to them. By Chomsky’s seminal 1957 proposal, Syntactic Structures, this breaking down was into two components, a ‘phrase structure’ component and a ‘transformational’ component. Within the latter, the rules manipulated variables. These could be added to, deleted, or reordered, giving what are recognisable as questions, negations, and so on, with all the elements minutely defined. These elements included the traditional category of tense, as in “She fell over” in contrast to “She falls over”. The novelty here was that all components were defined abstractly. The great empirical advantage of this abstraction is that it makes description precise. Some, like Ben Ambridge sneer at this on the grounds that it is ‘algebraic’. But without this precision, the finite learnability would not be possible.

Randulf Quirke (1972) drew attention to the therapeutic significance of this line of investigation as pioneered by Noam Chomsky (1957, 1965, 1968 and other work) and Eric Lenneberg (1969) with an appendix by Chomsky. But any inherited capacity is vulnerable. Hence speech and language defects and the website here.