Phonetics

The ultrastructure of speech sounds or 'phonemes'

Fine detail

A collaboration between phonetics and phonology

The model here

Late phonology

The phonetic alphabet

Fine detail

In contrast to Phonology, which studies speech systems as systems, phonetics studies the fine detail of the speech sounds or ‘phonemes’ of an accent or dialect or variety (or in some tradtional work the speech of an individual phonetician).

Phonetics tries to be as exact as possible. avoiding broad brush commitments such as the notion of universal features, or binarity. Phonetics prefers to measure points on scales of relative positioning, opening, protrusion, for instance, characterising the short, non-tense and the long, tense vowels of English, in terms of their actual length and tenseness, rather than the characteristic values for a system as a whole, such as the system of one particular sort of vowel. So, for instance, the short vowels in hid, head, had, sus, hod, wood, can be measurably longer than the ‘long’ vowels in heat, hate, heart, hoot. This is by the interaction between the voicing of the final consonant D and the adjacent vowel. In other words, phonetics prefers to measure values which may be gradient, rather than assuming any absolute, binary values. From this perspective, an overall system of sound systems is not even possible in principle.

A collaboration between phonetics and phonology

In 1988 the phonetician, Peter Ladefoged, collaborated with the phonologist, Morris Halle, on a study which proposed that the critical factor distinguishing the various constrictions of the vocal tract was not where they occurred, but which articulator was used to implement them. They characterised all sounds with the lips as ‘Labial’, with the front of the tongue as ‘Coronal’, and with the back of the as ‘Dorsal’. In his later work with Ian Maddieson (1996) Ladefoged lists six ‘active articulators’ in his 1988 terminology, although there is an uncertainty about whether the sixth should be considered an articulator. From front to back and downwards, they list:

- The lips;

- The ‘tongue tip’;

- The ‘blade’, around eight millimetres back from the tip;

- The ‘body’ which articulates against the soft palate and the ‘uvula‘, the protrusion about the size of a small grape, hanging down at the back of the soft palate, hence the Latin name;

- The root, not systematically used in English, but extensively used in consonants in many varieties of Arabic and the vowel systems of many sub-Saharan African languages;

- The glottis or vocal cords, used in all vowels in all languages, and in the glottal stop, widely used as an alternative articulator for T in many non-prestigious varieties of English, but in huntsman and other similar words in both ‘standard’ and prestigious varieties.

The speech and language therapy perspective

The articulators are soft, and behind the lips, almost invisible. But the musculatures can be manipulated with great speed and precision. The body of the tongue can be squeezed into a pit or a hump on demand. And the lips can be separately opened and protruded. A millimetre here or there and a few milliseconds sooner or later are all perceptible in their effects on any given phoneme.

From an acoustic perspective what matters most is the area function of the vocal tract at any particular point. Human mouths vary quite widely in the three dimensional shaping and the spacing of the teeth – if all the teeth are present. So ‘normal’ articulations vary quite widely too.

Largely for ethical reasons, there are limits on who can or should take part in experimentation. X-ray exposure is dangerous. So researchers may choose to experiment on themselves and take the risks rather than not experiment. At least two world class scientists have died almost certainly as a result of over-exposure to X-rays, Marie Curie and Rosalind Franklin, neither of them phoneticians.

For speech and language pathology, the greatest point at issue is with respect to consonants, sukch as the back of the tongue or dorsal stops in K and G, the fricatives in S and Z, the affricates in chew and jew, between the glide in you and the liquid in Looe, and between the other liquid R which, it is sometimes suggested, may be in the process of becoming a glide in English, and thus likely to trigger a variety of other changes, especially to L.

To a lesser degree, some children have issues with the vowels. Very rarely, this is the main issue.

What makes some sounds easy to say, and others hard? One diagnostic is how well second language learners cope with sounds in loan words and foreign names which do not occur in their native language. English speakers do not struggle with the TS in tsumami, pizza or Fritz. But many struggle with the first vowel in muesli in the original German. Swiss, Austrian pronunciation, with the tongue in the position for EE and the lips in the position for OO. Similarly, many second language speakers of English have great difficulty with the cross-linguistically uncommon vowels in rum and ram, both with the tongue relatively low in the mouth and keeping apart the vowels in rim and ream with the tongue high and at the front of the mouth, differing in their length or the extremity of this position. So native speakers often can’t tell whether second language speakers are saying ninety or nineteen.

The model here

Tellingly, against the idea that there is no universality, before the days of mobile phone apps, the writers of phrase books believed that no matter what language they were describing, its sounds could be categorised as some variation of the sounds of the language whose speakers the phrase book was designed for. If there was no universality, this would be absurd. Native speakers would have no idea what the second language speakers were trying to say, even if they sometimes have difficulty. And capital cities and tourist hot spots would have been littered with thrown away phrase-books.

But by the model of Nunes (2002), by the proposal here, and by the approach to S and Z issues discussed here under that heading, the apparent gradience of phonetics is by the ordering of derivations. Consider the case of S, with some sort of equivalent in most languages, but also problematic for many adults in many languages. How is this?

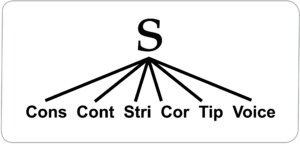

S involves these features. It is:

- A consonant;

- Continuant or a fricative, with an only partial occlusion of the airstream, not a stop;

- Strident, with a relatively high distribution of what is known as ‘aperiodic noise’ (as by the hiss of a kettle), as in sin, f in fin, sh in shin, in contrast to th in thin;

- Coronal, or with the front part of the tongue;

- With the actual tongue tip kept flat, with no grooving or fractionally further back articulation, as by sh in shin. (There is variation across speakers as to how much the tongue is grooved or the articulation is ‘backed’. I personally use highly non-standard configurations, with extreme grooving for sh, and for s, with the articulation ,not with the actual tongue tip, but further back. Speakers evidently accommodate to the anatomical configurations of their mouths, with no linguistic significance);

- Voiceless, with the vocal cords apart, as in Sue in contrast to zoo.

This could, in principle, be represented by a six way branching.

But no phonetic theory postulates anything like this. Many theories just eliminate the consonantal feature and collapse stridency, coronality, and the tongue tip quality into one, giving a three way branching. This entails a very elaborate theory of possible articulations. But by the model here, a three way branching is ruled out in theory, because it conflicts with the much more advantageous principle of recursive branching at most two ways, as shown below and in Nunes (2002).

The branching can recur any number of times. But with any number of binary features, the ordering is the factorial of that number. With six features, there are therefore 720 logically possible orderings. It may be that most of the logically possible orderings are ruled out on some combination of articulatory, perceptual, or conceptual factors. For instance, the consonantal feature may be forcibly first, to give meaning to all the other elements in the sequence. But there is no obvious, a priori reason for any particular ordering with respect to the voicing feature, except that its property of defining a timing relation with some other feature cannot be implemented before that feature is defined, and it cannot have evolved before that feature, or the evolution would not offer any advantage.

Nunes (2002) shows the clinical advantages of resurrecting, redeveloping and updating Diana Archangeli’s 1984 theory of underspecification. It offers a simple, natural account of the two commonest sorts of lisp, fronting – saying car as TAR, and only very rarely two as COO, and the oddness that in early, typically-developing speech, a tongue tip articulation assimilates to a back of the tongue articulation in doggy as [gogi], and never as [dodi], and, as full competence approaches, this relation is reversed, with calculator as [KALTERLAITER], and never as [KALKERLAIKER].

By this theory, only one value of a binary feature is used in the mental representation of a word. For the sake of maximality, these orderings may sometimes interact with the syllable structure rules. In the limit, the only entry for a consonant is for consonantal as in the first sound in string and the last sound in next. s is only possible sound if there are two following consonants before the vowel. t is only possible sound if there are two preceding consonants after the vowel, in next k and s, written as X. Default rules supply the rest of the matrix of the pronounced form in both cases – as continuant s in string, and non-continuant t in next.

In the third person singular and plural morphology, for s in computes and t in developed, the only entry is for continuant in the first, and for an unmarked element in the second, with only one possible pronunciation. Again, the rest of the matrix is by default.

One advantage of this model is that it offers a way of describing what is happening in a chain vowel shift taking four generations to complete, as described by William Labov (1994 & 2001), in the USA today, but seemingly similar to what happened by the ‘Great English vowel shift’ as this was called by Otto Jespersen, between the times of Chaucer and Shakespeare. Before the shift a vowel has one value. And after the shift is has a different value. Main was pronounded more like modern mine before the shift. And then over two hundred years or so, the articulation gradually changed with the position of the tongue getting higher and higher, but so slowly that the only way of detecting it would have been by comparing the pronunciations of the very old and the very young. And even that comparison would not have revealed the whole span of the change.

By the model here, those leading the change started changing the derivational order of the vowels by a single term, not enough to be obviously detectable, but enough that it could be unconsciously copied by others. As the changes were multiplied in the same direction from one generation to the next, the vowels slowly changed. If Shakespeare could have heard Chaucer talking, Shakespeare would have found Chaucer very hard, if not impossible, to understand.

Of necessity, the ordering here has to be learnt in full and from scratch, with the ordering critically significant. How does the child learn the ordering here? What clues are there in the spoken language? Nunes (2002) proposes that the child is sensitive to variation within the speech of individuals and across the speech patterns of different individuals. The greater the variation the later the derivational point at which it is happening.

The full application of the relevant principles is complex because of the complexity of English syllable structure on the one hand and English prosodic structure on the other, both relevant in calculator.

A sensitivity to variation is testable in the lab. It will be my next project.

Late phonology

Putting things very briefly, by the approach here, in a way which has been said many times before, I contend that phonetics is late phonology. But with the sometimes fractious relation between the disiplines, this characterisation may be regarded as itself contentious.

The phonetic alphabet

The term, phonetics, is used to define International Phonetic Alphabet, designed to represent the sounds of any language, either underpinning or contradicting any notion of universality.

See also Features, Phonology, Phonotactics and Syllables