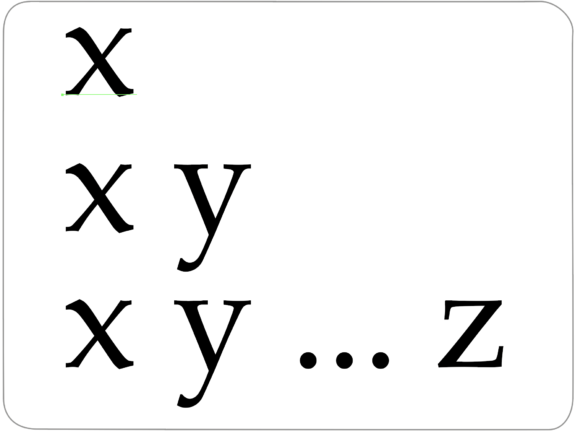

Discrete Infinity

Building an infinite set of structures from a finite resource

Between two and three

A counter-claim

Between two and three

The number of phonemes or sounds in a language and, at any given moment, the number of the entries in anyone’s lexicon, is finite or discrete. But the number of ways in which they can be combined is infinite. This is known as ‘discrete infinity’, discrete because the structure is built from a small, finite number of elements, infinity because the number of possible sentences is infinite. By the proposal here, the first indications of this normally start to appear in child language between two and three.

The idea of discrete infinity was originally developed by Wilhelm von Humboldt (1836), published a year after his death.

Consider these:

- You lie.

- You know her.

- Who do you know?

- You seem to know her.

- Who asked who you seem to know?

- We know who asked who you seem to know.

- You think (that) we know who asked who you seem to know.

- I suspect (that) you think (that) we know who asked who you seem to know.

- I’m sorry to say (that) I suspect (that) you think (that) we know who asked who you seem to know.

And so on. A simple sentence can be extended indefinitely. We can go on multiplying the variations any number of times. This is is known as ’embedding’ or ‘recursion’ (or more traditionally as ‘subordination’. Structure is ‘derived’ from the most deeply embedded part of the structure – reversing the idea by the traditional term of ‘subordination’. As the derivation proceeds, the sentence gets harder to understand, but there is no point at which it ceases to be English. And not just English, but any one of the other seven thousand or so languages spoken around the world. Significantly, it was Humboldt who started to expand the set languages under general purview from Latin, Greek, and Hebrew, only the last unrelated to the languages of Europe. Humboldt started with Basque and Javanese.

In a very approximate way, the repetition of the same sort of structure is known as ‘recursion’.

The same functionality allows humans to use a finite number of symbols, the sounds or ‘phonemes‘ of the language or the signs of a signed language, to say an infinite number of things and be understand by any other native speaker or signer.

No non-human has ever shown evidence of anything like discrete infinity. To this extent, humans are both unique and exceptional in the animal kingdom. But for some reason, the exceptionality of human language is strongly resisted by some. But to me, the onus is on those who deny any sort of genomic explanation to provide a more plausible explanation of discrete infinity.

This is not to suggest that children are born knowing how to talk, a self-evidently absurd aunt sally sometimes peddled by those opposed to any idea of human exceptionality or specific genetic endowment. The claim here, is just that children come to the task of learning language as though expecting to find structures which make discrete infinity possible. Exactly how this happens has been at the centre of linguistic research for the past 70 years by a project which originates in the work of Noam Chomsky. It is the main focus of the proposal here.

The linguist, Stephen Anderson, sets out the issues here in his justly famous 2006 book, Doctor Dolittle’s delusion. It is scholarly, but completely accessible and non-technical.

When the apparatus here is fully developed, normally around ten, this allows an infinite number of structures, known as sentences, to be built from a finite number of elements, the speech sounds of the language. The ccompositionality is based on words and parts of words not just in order, but in a structure ensuring that the words have a meaning that goes beyond their meanings other than by the structure.

A counter-claim

One linguist, Daniel Everett, claims that there is a language, Pirahã, which disallows even the first step of embedding. He claims that Pirahã speakers never refer to anything other than what is currently in the immediate frame of reference. Pirahã is spoken by a Brazilian tribe of less than 500 people living on a remote tributary of the Amazon who had studiously avoided contact with the outside world until Everett persuaded them to allow him and his family to join them. On Everett’s account, Pirahã speakers can hardly discuss or question reports of untruth with any nuance because their language makes this impossible. Really? Until Everett found them, the Pirahã had taken good care to remain uncontacted. Everett’s account of Pirahã is cited approvingly by Tom Wolfe (2018). But Everett’s account is demolished on both theoretical and empirical grounds by Andrew Nevins, David Pesetsky and Cilene Rodrigues (2007). The notion of univerality is simpler than the claim of near universality with one exception. I adopt the simpler claim here, rather than the more complex claim by Everett, querying a generalisation which holds of every other language in the world. Everett’s data concerns a language which is clearly very threatened. As a language approaches the point which Pirahã is now sadly at, it often loses key aspects of its grammar. This is noted about languages much less threatened than Pirahã. Everett’s claim is thus highly suspect.