Irregularities

Universals, and Universal Grammar

Hidden by the way language evolved

The irregularities of language are obvious in contrasts like fall and fell, stand and stood, and be, am, is, was and were. These are often taken to be ‘the grammar’. But there are also REGULARITIES which are not obvious at all. By the framework and the proposal here, some of these regularities are by universals which are hidden by the way human speech and language have evolved – by a series of highly-specific steps. These hidden regularities are commonly referred to as ‘Universal Grammar’ or UG.

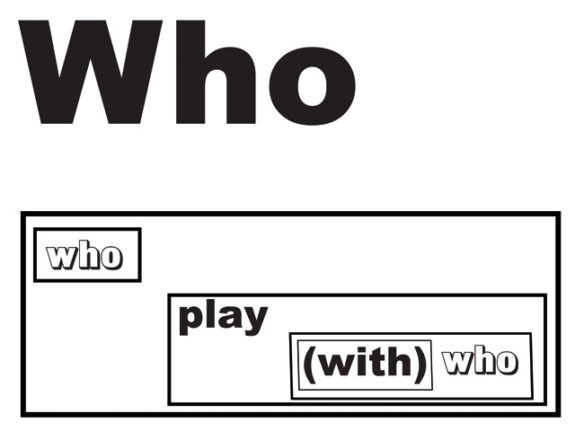

Some of the hidden regularities are first confronted by language learners in questions they hear with who, what, where and other such words, pronounced on the left edge of the structure, , and understood somewhere else. This sort of displacement appears to be universal across human language.

A child on his or her first day at school may be asked “Who do you want to play with?” or “Who do you want to play with you?” In one sense, they mean much the same. But in the underlying structures, who relates to different elements in different positions. So competent speakers understand the two questions in correspondingly different ways. Although the difference is by only by you as the final word in one, but not the other, the onus in any response is quite different in each case. A child might seem to respond appropriately to questions of this sort without making the analysis of a fully competent adult speaker. Such an analysis involves putting together two of the principles which the child first starts to master much earlier – typically in the first three years, by the proposal here.

Words like who are copied from various positions in the structure other than those where they are eventually pronounced. Forcibly there is a derivation. This is not taught in school. Nor could it be. But native speakers of English understand the principles of this derivation accurately and reliably and without a word of instruction.

The grammar on this point involves not one, but five sorts of universal.

- By what is known as ‘case’, in English, as in most languages, a difference is marked between she and her in “Who does she want to play with her?”

- By what is known as ‘person’, the reference to the speaker, or the listener, or anybody other than the speaker or listener,

- By what is known as number, she is differentiated from they. Number and person are both features of the meaning, reflected in whether do is said as does.

- By what is known as ‘inflection’ or ‘tense’, in “Who does she want to play with?” or “Who did she want to play with?” with do and did denoting different times.

- By the contrast between words used as verbs like play, and elements known as ‘functors’ like do, does or did, whose only role is in relation to one or more other parts of the structure. All languages divide their words into these two main categories, functors on the one hand and what are traditionally known as ‘parts of speech’ or ‘lexical items’ in the framework here, on the other.