Voice

The vocal cords (or folds) and hoarseness

Voice uses a function which evolved to allow an air breathing animal in the middle of feeding to suddenly sprint – to catch the next meal or avoid becoming one – without getting food into the lungs. The function is vulnerable in various ways.

I treat those issues of voice where my expertise is likely to be relevant and useful – not all issues, but some.

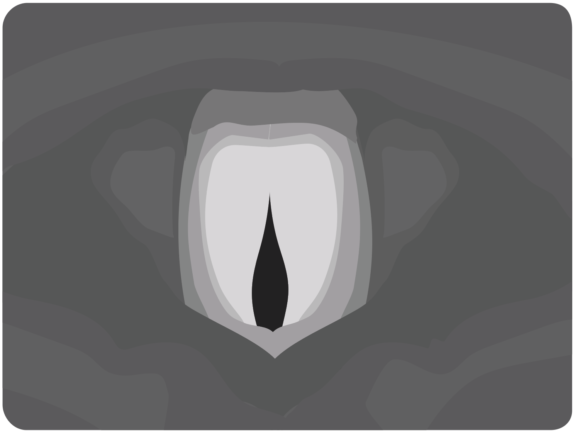

The voice box is a mechanism in the throat, halfway between the lungs and the mouth. The vocal cords are lumps of cartilege suspended by muscles which can brought tightly together to form a valve sealing off the lungs. They are hinged at the front inside a larger lump of cartilege, forming the larynx. They are known as the vocal cords, because voice now appears to be their main function. The tension along their length and the position of the voice box in the throat can both be adjusted to change the pitch of the voice.

If the vocal cords are brought close together but not actually touching and in a given state of relaxation along their length and air is breathed out through them, they vibrate. In slow motion, the vibration of the folds is like the fluttering of a flag or or the wave action of a whip. The chords ‘roll’ together, and roll apart. The rolling action is along their length. This creates a buzzing sound which is then modulated as it passes through the upper part of the throat and the mouth. The resulting sound is what we know as ‘voice’ in humans, song in birds, croaking in frogs.

The pitch of the voice is raised by increasing the front-to-back tension of the vocal cords and raising the larynx in the throat. Singers know combinations of these things as different ‘registers’. Everyday use in speech and in untrained singing involves variation within around an octave, equivalent to the notes at the top and bottom of the neck of a traditional acoustic guitar.

But the structures evolved for an entirely different purpose. And the fact they did not evolve for the way they are now used may be connected to their vulnerability.

Animals which feed and breathe through the same opening, including amphibians like frogs, reptiles like lizards, birds of all sorts, and mammals, including humans, all need a way of ensuring that the food does not get into the structures for getting oxygen out of the air – the lungs. They do by two valves, the epiglottis and the larynx. The larynx or ‘voice box’ holds the vocal cords which evolved to protect the lungs of air breathing animals, and do so continuously throughout life from birth to death. Any interruption of this function is fatal within minutes. Food is less critical. And voice even less critical. But one can become hoarse, with almost no useful voice, in just a couple of enthusiastic hours supporting one’s team in some sport. Prolonged hoarseness can lead to polyps or nodules forming on the cords. Smoking can lead to cancers. All of these are using the larynx in a way for which it did not evolve. Most of these ill effects can be prevented by prompt and early intervention in the form of speech therapy and resting the voice.