Features

In language

Contrasts

In the sound system

For vowels:

For consonants:

Simplifying the feature system

Derivation?

A small problem

Alternatives

In the assembling of words into phrases and sentences

In the morpho-syntax

In the vocabulary or lexicon

Accurate repetition

Contrasts

Human language is built from contrasts between one linguistic element and another. The contrasts are expressed by features. How these contrasts arise, how they are learned, and what difference this makes to the learning process, are all disputed. But the reality of the contrasts is beyond dispute.

The features are of different sorts, distinguishing nouns from verbs, one sort of noun from another, consonants from vowels, the denotation of intense love or disrespect, and so on. Of course, the mind can distinguish any number of shades of grey or points in the metamorphosis of a square into a circle or the other way round. The metamorphosis can be by rounding the corners, or by curving the sides. But for the purposes of language, the features are absolute or discrete. A square is a square. A circle is a circle. There are no points in between or half way houses.

There may have been a precursor of a feature in the mind of the first stone tool maker. A suitable sort of stone had to be chosen and chipped with another stone to form a sharp edge, with facets at angles to one another. Sharpness was a feature in the mind of the first stone tool maker.

By the proposal here the first step towards speech and language was to apply this human-specific cognition to all learnable aspects of the relation between physical acoustics and meaning – speech and language – in the sound system, in the organisation of the lexicon, in the ways words are put together into sentences, and more controversially in the organisation of semantics.

In the sound system

It is obvious that speech has to be articulated and perceived and that the signs of a signed language have to be formed. This is part of what generative linguists call the ‘externalisation’, as an irreducibly necessary part of the system. For speech, this involves gestures at various points in the vocal tract at which it can be narrowed or widened. So the vocal tract is like a wind instrument with the interesting property that the bore can be varied along its length, not infinitely, but more than in any instrument of the orchestra.

On most inventories of the sounds of speech, or ‘phonemes’, in what is supposedly ‘Standard English’ or ‘General American’, there are 44 of them. ‘Inside’ the phonemes it is ‘distinctive features’ which distinguish toe from doe by a variation in two timings in relation to one another. One feature is known as ‘voicing’. Another is known as ‘aspiration’. Voicing involves the bringing together of the vocal folds to vibrate against one another soon after the release of the closure in the mouth, by the tongue tip in D, by the back of the tongue in G, and by the lips in B. A significantly greater delay is known as voicelessness, as in T, K, and P. Aspiration is by a further increase in the delay. In English this happens where the phoneme occurs on its own at the beginning of the syllable, as in tea, key, and pea.

Another feature differentiates between closures of the vocal tract where the passage to the nose is closed and those where it is left open. Another differentiates between phonemes where the vocal tract is completely closed as in P and B, and those where it is almost closed as in F and V. Other contrasts between phonemes can be defined in terms of a small number of other features. Thus phonemes differ by where they are articulated in the mouth, how they are articulated and resonated, what else is happening in the vocal tract, and when, and how they fit into syllables.

But even though all of the variations here are by degrees, with the difference between P and B expressed by different timings of the release of a closure in the mouth and a change in the separation of the vocal cords allowing them to vibrate spontaneously against one another, they are perceived as distinct categories. How the categories are built in the mind is plainly something which has to be learnt. As child speech shows, this is plainly not easy.

For our purposes here, the following features (broadly, but not entirely) from Chomsky and Halle (1968) or SPE are enough to keep the phonemes of English apart from one another.

For vowels:

- Where the tongue is in the mouth – up at the top, down at the bottom, or in the middle, towards the front of the mouth or at the back;

- Whether the tongue is tensed and as close as possible to the edge of this space;

- Whether the vowel is long, usually, but not always, as a secondary character of tenseness – or the other way round (the order of definition is disputed);

- Whether the tongue moves from one position to another, as in the case of the diphthongs in high and how,

- Whether the lips are rounded as in rue and raw, or not as in hay and high;

- In a way that Chomsky and Halle could not reduce to first principles because their framework did not refer to the syllable, whether the segment is classified as a vowel, and thus potentially a syllabic nucleus.

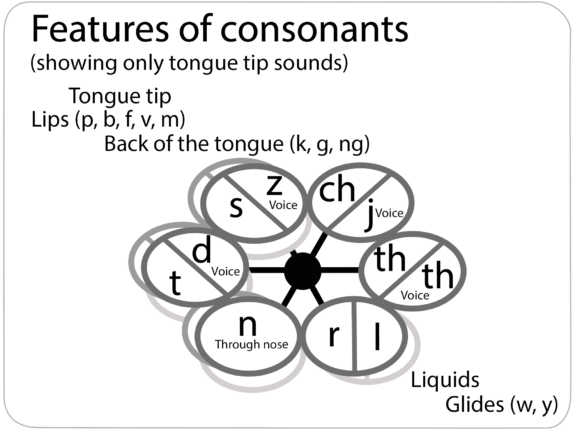

For consonants:

As sketched in the diagram above. the feature system of consonants is most easily imagined as a three dimensional mattrix.

The main articulator is the tongue tip, capable of faster and more precise articulations than any other part of the vocal tract. Most of the functional system, in do, did, verb singular and noun plural S, is by tongue tip articulations. In the diagram above, only the tongue tip articulations are shown as the sounds they form.

- Whether the sound has no intrinsic syllabic role, as is typically the case, but not invariably as in the English ‘syllabic L’ in little, middle, and such like, where the sound is the ‘nucleus’ of the syllable, a role typically played by a vowel;

- Whether the sound is characteristically part of the left edge of a vowel like Y and W in you, tune, why and twice, known as glides or semi-vowels;

- Whether the sound is invariably next to the vowel in clusters like the L and R in splash and spray, traditionally known as liquids;

- The continuance of the airstream (distinguishing T from S) – whether the airstream is continuous or not, where sounds like T are generally characterised as ‘stops’ because of the totality of the closure, and sounds like S are generally characterised as ‘fricatives’ because of the air friction from a partial closure;

- The place of any constriction – whether the airstream is ‘stopped’ or ‘bottle-necked’ at the lips, or with the tip of the tongue, or the back of the tongue (distinguishing T from P and K);

- Whether the airstream is initially stopped and then just partially released as in the cases of the initial sounds in chore and jaw;

- The relative timing of any involvement of the vocal cords (distinguishing ‘voiceless’ or ‘unvoiced’ T from ‘voiced’ D, P from B, S from Z, CH from J). On account of this difference, B and D are known as ‘voiced’ with the vocal cords allowed to vibrate together relatively soon after the closure in the mouth is released, and P and T as voiceless, with a significant delay between these events

- In the cases of voiceless stops, whether the delay in the voicing is increased by what is known as ‘aspiration’, as in pie, tie and cow in English, but not where the stop follows S, as in spy, sty, and scow;

- Whether the airstream passes through the nose (distinguishing N from D);

- Whether the main effect is to constrict the airway or to resonate, with this resonance, or what is known as ‘sonority’, characteristic of L, R, N, M, W, Y);

- In the case of fricatives, whether the ‘noise’ falls below a given frequency, as it does with TH (distinguishing TH from S, F, and SH);

- In the cases of S and SH (both with the tongue completely inside the mouth) S, unlike SH, makes the constriction with the tip or apex of the tongue.

In the cases of buy and die, there are the same openings and closures within the mouth, at the lips for B and with the tongue tip for D, but without any opening of the sphincter, So B and D are known as ‘oral stops’. In pie and tie, the closure is released momentarily before the vocal cords are brought together to vibrate against one another. There is a slight puff of air in P and T which does not happen with B and D. This difference can be easily detected with a match or a candle.

But the learner has no privileged information about his or her target language, with its phonemes exclusively defined in this way.

On a featural account of the inventory such specificities have to be represented as one aspect of what Marlys Macken (1995) called the ‘learnability space’.

Simplifying the feature system

Ken Stevens and Sam Keyser (1989) propose that some aspects of speech have the special role of ‘enhancing’ contrasts, like the rounding of the lips in the case of vowels articulated with the tongue at the back of the mouth, like those in woo and war. This has the important effect of simplifying the feature matrix of speech sounds. But the learner has to work out which features are part of the underlying definitional matrix and which ones serve to enhance the acoustic distinctness of a given sound. This is critical, I propose, to the understanding of why S is so commonly problematic in diverse languages.

Derivation?

There are two mutually irreconcilable theories of what is going on here. By one theory, essentially taxonomic, proposed by John Wallis (1653), speech sounds can be CLASSIFIED by their properties. By the other theory, proposed by William Holder (1669), the phonemes are DERIVED from their properties, in other words going back to their origins.

300 years on, the issue still haunts research in both linguistics and speech and language pathology. Only now, the issue from a speech pathology perspective is mainly cast in terms of the clinical utility and relevance of the generative approach to linguistics associated with Noam Chomsky. Proponents of the generative approach (like me) assume a derivational model, with the phonemes derived from features. Those opposed to this approach tend to insist on the centrality of the phoneme, seeing features as just the necessary properties of classification. The rather subtle difference here is no minor quibble.

A small problem

The original evidence for features was from changes in pronunciation was first pointed out by William Holder in 1669 mainly with reference to the speech of one child, then by the Danish linguist, Rasmus Rask, with reference to changes in the pronunciation of European languages over hundreds and thousands of years, and then developed and popularised by the German Jakob Grimm of fairy tale fame.

Thus it was noted that the TH in English father was originally a T as in German vater, Latin pater, Greek pateras. The R in Portuguese obrigado (thank you) and branco (white) were originally L as in English obliged and blank. All of these changes were by single features.

But how does this happen? These seemingly categorial changes from one phoneme to another, changing the value of one feature, would at the very least be commented on, if they didn’t lead to outright misunderstandings in a speech community. The problem is that there is no evidence of this happening, not in the historical records, and not by careful and detailed observation of such changes where these are demonstrably happening in the modern world.

William Labov (1994, 2001) describes some comparable vowel changes happening right now in the USA, using tape-recording and very large amounts of data which could only be processed computationally. As Labov shows, the variation is by less than a whole feature. The change from one vowel to another takes place over four generations with nobody noticing the subtle changes in the speech spreading through the population.

There are various theories about how this might happen. By one, the phonetics is scalar and non-categorial. But this entails that the child learner has to be listening out for two different sorts of things, one scalar, one categorial.

The solution, I believe, is by an extended notion of what Chomsky and others call ‘Merge’, applying this to the features, so that categories can be ‘built’ from features, but in language-specific or perhaps more accurately dialect-specific or even idiolect-specific ways. I sketch this in my proposal here. But the idea needs a great deal of laboratory work which I have yet to start).

Alternatives

By the taxonomic model, the consonants are grouped into three ‘systems’, involving:

- Place of articulation, with at least these possibilities exploited in English, the two lips, the upper lip and the lower teeth, the tongue between the lips, the tongue against the flesh ridge behind the upper teeth, the tongue against a broader area slightly further back, the back of tongue against the back edge of the soft palate, known as the ‘velum’

- Manner of articulation, differentiating stops with a complete blockage of the airstream from ‘fricatives’ with an almost complete blockage, differentiating both of these from ‘affricates’ as in church and judge, starting with the complete blockage and ending in a partial blockage at the same point in the tract. differentiating ‘nasals’ with the airstream passing through the nose, M, N and the sound at the end of sing and ring, differentiating ‘lateral’ L with the airstream passing around both sides of the tongue and R with the tongue curled or grooved, the glides or semivowels, Y and W, always just before a vowel in English (despite the spelling of how and toy, residues of an earlier English);

- Voicing, differentiating stops and fricatives according to whether the vocal folds are allowed to vibrate during the blockage or very soon after it, or not.

By another alternative, known as Articulatory Phonology, features are independent of what SPE calls segments or what are conventionally represented by written letters. Phonetically, the opening of the naso-pharyngeal sphincter (the gap between the throat and the nose} does not coincide with the positioning of the tongue and the lips for an adjacent vowel. Rather the sphincter remains open as the vowel articulation begins or it anticipates the consonant where the consonant follows the vowel. In a word like man or name the sphincter hardly closes. Articulatory Phonology generalises across this and other similar cases.

There are, I believe, many reasons for rejecting both articulatory and taxonomic models. Six of the strongest are as follows:

- Models with at most two values for every feature correspond to the basic mechanism of the nervous system which allows only activation or non-activation;

- Alternative models do not give a good account of common forms of incompetent speech in diverse languages, for instance, characteristically losing one feature in diverse forms of lisp;

- Alternative models do not illuminate the cross-linguistically typical situation where just three or four cases contrast with one another, as in English, and falsely predicts systems contrasting any number of places of articulation;

- Alternative models make it hard to explain what is going on when a phoneme shifts from one category or part of a system to another, as in the case of R which seems to be shifting to a glide in those varieties of English which do not allow it to occur after the vowel – at the end of a syllable;

- Alternative models do not give a good account of the common parentage of modern German Vater and modern English father, differing by only one or two features in each of the two onsets;

- Alternative models do not give a good account of the complex dialectology of the NG pronunciation in sing, singer, singing, in different parts of Northwestern England.

In the assembling of words into phrases and sentences

Semantic or what are known as ‘interpretable’ features involve:

- Singularity and plurality or ‘number’, differentiating house from houses, book and books, or the irregular man and men, woman and women, child and children, in all cases triggering syntactic agreement as, in the regular cases with ‘S, in the difference between “there IS a book on the table” and there ARE books on the table” or “The book is on the table” and “The books are on the table”;

- Gender or sex, differentiating he from she;

- Person, differentiating I, you, he and she;

- ‘Animacy’ in the difference between it, on the one hand, and he and she, on the other;

- Human animacy reflected in the use of who only with reference to humans.

Formal syntactic or what are known as ‘uninterpretable’ features include the notion traditionally described in terms of subjecthood, as in the ‘subject’ of a sentence, as in he in “He likes her.” This is assumed in the framework here, but it is given less importance in other frameworks.

In the framework here, it is the interaction between these two sorts of features which gives the important notion of agreement between:

- Different parts of single clauses, as between I and am in “I am young”;

- Are and crimes against humanity as in “There are crimes against humanity”;

- What were once a subjunctive and a tense in “If I WERE you, I WOULD tell the truth” where would was once the past tense of will.

The purpose of this rather subtle apparatus is to give a single account of these phenomena, as opposed to just stipulating them, with the consequence that each such stipulation has to be learned.

In the morpho-syntax

In most languages, but not the most widely spoken varieties of modern English, there are two or more ways of saying you, according to whether there is implicit respect for the addressee. In the English of parts of the English Northeast, the older thee, thou and thy are retained to denote familiarity and affection.

In the vocabulary or lexicon

In many languages, including English, any reference to the addressee including the word, old, as in old boy, old man, old fellow, implies affection or familiarity or a lack of respect where this might be expected. Terms like fellow and clique, as a loan from French, or references to a theory as a story or a saga, or references to a person kipping, ambling, whittering, lurking, etc., have the same effect. References to a woman as any sort of non-human have connotations ranging from the disrespectful to outrightly insulting. It seems that children only start to become aware of this aspect of language from the age of around three.

Accurate repetition

Whatever the theoretical account of changes in speech over single lifetimes, the normal acquisition of a particular accent at a particular point in time is extremely accurate, with only the slightest deviations noticed and remarked on, usually negatively.