Syntax

Helping to make meanings exact, and knowing what is nonsense

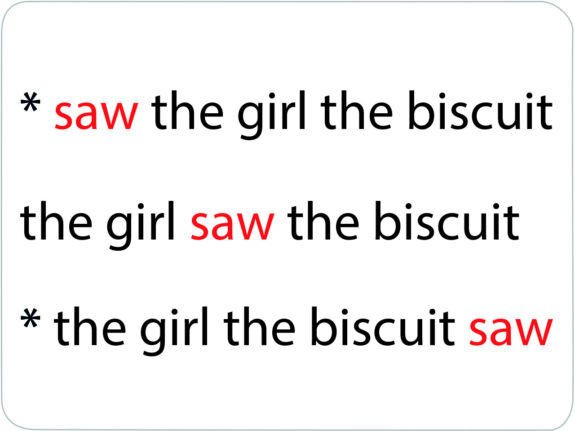

Across the world’s languages, the ordering of the words in the sentence “The girl saw the biscuit” is less common that the order in “The girl the biscuit saw” but commoner than the order in “Saw the girl the biscuit”. Only one of these makes sense in English. The others are nonsense, or ‘ungrammatical’ in standard, syntactic terminology, and accordingly shown with stars or asterisks. “The girl the biscuit saw” would make sense with reference to some girl in a make-believe world of seeing biscuits. But in the real world, where only animate creatures can see, it just makes no sense.

Syntax determines whether the way words are put together makes sense, or not, and, in this case, whether one of these orderings is favoured or can be ‘coerced. In this case there is no favouring or plausible coercion. Then case is clear. There is no difference here in logic. All three orders are equally logical, as are the much rarer cases with the biscuit first and the the girl last. Other languages, such as Russian, order the equivalent words more freely, with changes in the meaning. In English one order is strongly forced by syntax. So the ordering of the main constituents of a sentence is relatively easy for English children to learn. And English children mostly get this ordering right as soon as they start combining the words – usually leaving out the word the.

In English, as in all languages, there are various ways of subtly changing the emphasis, as by “The biscuit was seen by the girl” or “What the girl saw was the biscuit” or “It was the biscuit that the girl saw”, all of these only learnt long after the simple order.

Syntax thus helps to make meanings exact – but only helps. Syntax can also create double meanings, as by Noam Chomsky’s now famous example “Flying planes can be dangerous.”

For most varieties of English, in the grammar of putting words and parts of words together to form phrases and sentences, the syntax takes account of both the order of the words and their forms. The term syntax is from ancient Greece. Here the learner finds:

- Relatively fixed word order with prepositions before the word they govern as in “on Monday” and with verbs before their ‘complements’ as in “saw the biscuit”, but with the opposite order in “a man eating tiger”;

- A very intricate ‘auxiliary’ system with have, can, do, may, and the past tense forms had, could, did, might, ought (from owed) with varying meanings, involving permission, possibility, time and relevance to the present, and negation, question formation, variations in the agency by the use of the ‘passive’, as in “She might have been being swindled” – by complex manipulations of the structure. The main manipulation obvious to small children learning English is the position of words like can in statements like “You can do that?” and questions like “Can you do that?” and negative questions like “Can’t you do that?” On the simplest analysis, the relation between these forms is expressed by a DISPLACEMENT.

- The words who, what, which, when, why, how, all pronounced on the left edge of the sentence in simple questions, as in “Who did you see?” or on the left edge of the clause in ‘indirect questions’ like “I know who to see”, but with a quite different meaning otherwise, as in “You saw who?”

Most of the meaning of phrases and sentences is encoded in these ways.

In English a small number of forms, S, Z and IZ, denoting plurals and present tense, T, D, and ID denoting past, and ING denoting a continuity, attach inseparably to the right edge of a root. Eight or so systems giving a total of a few hundred irregular verbs like sing, teach, fly, similar in number and complexity to equivalent systems in French, German, Spanish, Italian, Greek, Russian. In English there are just three irregular plurals – in men, women and children.

The main semantic load is thus on the syntax, with the morphology of plurals, past tenses, and continuous forms carrying only a small part of the load.

In languages like English, meaning is mainly encoded by the order of the elements, known as constituents, or more specifically what are known as the ‘subject’ and ‘object’ with respect to the verb. English is particularly simple and rigid on this point. So with the child, the dog, and walked, as three constituents, “The child walked the dog” and “The dog walked the child” are both interpretable as sentences. But with walked in any other position, the structure is no longer interpretable. The significance of the subject and object roles is pointed up when these roles are expressed by pronouns, as by”I walked her” and “She walked me”, with the form varying between I and me, she and her, according to the relation between them.

English is characterised as a Subject Verb Object or SVO language. This is not the only possible order. There are slightly more SOV languages. VSO languages are unusual. The other logically possible ordering are rare, in some cases very rare. But these are points which the learner has to attend to. Most languages allow some freedom with respect to word order, as in “The dog, I walked yesterday’, said as a statement of fact, a complete sentence, with an emphasis quite different from “I walked the dog yesterday”. The main freedom with respect to word order in English is with to adverbs like yesterday, fast and slowly, and adverbial phrases like down the road, in seventh heaven, and so on. So “I walked the dog yesterday” and “Yesterday I walked the dog” are both possible with other orders with other adverbs in other structures. But only in very small number of languages is it possible to break up the constituents, other than to express some very marked meaning, as by “I walked the yesterday dog”.

In the framework here, displacement is pervasive in human language. For language to be learnt the way it demonstrably is, fast and reliability, learning must proceed on the basis that the learning mechanism is highly sensitive to any evidence of displacement.

Displacement and other phenomena of syntax are quite different from the much less systematic but far more extensive processes of discourse.

Expressive and receptive language

By a distinction largely dictated by psychologists (rather than linguists), many tests of language development distinguish between ‘expressive language’ and ‘receptive language’, using different criteria according to what is being tested. Small children can often identify exotic animals from their pictures long before they start using the names, and respond appropriately to instructions before they give equivalent instructions themselves. But in my view this is not sufficient to force the conclusion that expressive and receptive language represent separate areas of cognition. The apparent discontinuity with reception before expression in almost all areas of language in almost all children may be due to any number of intervening factors – including memory, familiarity, and the demands of the context. It is also possible, as the framework here would dictate, that there are just different degrees of competence, yielding different results according to how these are tested.

In other words, tbere may be no such thing as an ‘expressive language disorder’ as a well-defined cognitive defect.

It might seem possible in principle to devise a fully symmetrical test of expressive and receptive language. But in the absence of such a thing, the difference here may be artifactual. Tests of ‘expressive’ and ‘receptive’ language may may be just tapping different capacities.

Putting things differently, there would seem to be limits to what can be shown by psycholinguistics.