The tragedy of English spelling

Too many cooks

English represents a unique mix of languages, each incorporated at a particular time, in a particular section of society, in one case more than once. Each of these incorporations is reflected in the spelling. But each incorporation was designed to suit the needs of readers familiar with one system in relation to another system. At the time of Shakespeare there was no clearly agreed standard. Shakespeare spelt his own name in various ways, sometimes on the same page. After his death a spelling standard gradually emerged. But the system was ad hoc. It’s not that there isn’t a system. It’s more that English spelling uses a number of different systems which don’t fit together.

It’s now probably too late to go back to the drawing board. But it’s worth tabulating the problem, if only to protect learners from simplistic non-solutions like ‘Systematic Synthetic Phonics’.

Back to King Alfred

King Alfred was the youngest of four sons, and thus not likely to become king. But evidently he was thought to be clever, and in a most unusual way at the time, as a small child, he was sent to Rome to be educated. In the event, all three of his older brothers were killed one after the other fighting the invading vikings. And Alfred became king. He was a man of the most incredible personal bravery. To spy on the invading army, Alfred pretended to be a wandering minstrel. What the vikings would have done to him if they had rumbled his true identity does not bear imagining. He must have been, as well as all his other talents, a quite reasonable singer.

The English of Alfred’s time, now known as Old English, was in the process of becoming a fusion of the Norse of the Vikings and ancestral forms of German and Dutch. The Norse effect was stronger in the North, the main centre of Viking colonisation, and less favoured in the South. Over 1,200 years later, there is still a North-South divide between accents, roughly along the frontier which Alfred negotiated with the Vikings from the River Lee in East London to the Northwest.

Knowing Latin well, Alfred became a significant scholar in his own right. But he encouraged the use of Old English in public life and official documents. He founded what is now generally referred to as the ‘Anglo-Saxon chronicle’, a record of the main events of the year, crucially written in what was then the main spoken language, rather than the more prestigious Latin. And he translated into English a famous book at the time, written 100 years earlier, now known as The consolations of philosophy by Boethius, a scholar / diplomat, while awaiting execution, knowing that this would be painful, bloody, and prolonged. The book sets out in prose and verse the limitations on power, but crucially without reference to religion.

In Alfred’s English there were new letter forms for sounds like the TH sounds in modern THIS and THINK, with no equivalents in Latin.

1066

With the Norman Conquest in 1066, the priorities of the new king, William, were power, control, authority, and revenue, but not culture. William brought with him Latin-speaking bureaucrats to run what quickly became the most highly-controlled state in the known world.

William and his descendants spoke a fusion of Viking Norse and the French of Northern France at the time. This endured for 300 years as the language of the court and the aristocracy.

So there were three main languages, the Old English of the conquered people, itself in the process of a fusion, the Norman French of the new rulers by another fusion, and the Latin of the new bureaucracy, itself becoming less classical and more a form of an early romance language – modern French.

For the sake of trade and administration, means of communication had to be found, creating career and business opportunities for those able to speak more than one of the three languages. But the new bureaucracy had no interest in English or in preserving any of its characteristic (and well-designed and useful) letter forms. Alfred’s approach, giving preference to English, was duly abandoned.

So we now have sheep and cow from the Old English of the producers of the animals and mutton and beef from the Norman French of the buyers.

English as an extreme case of a ‘contact language’

For 300 years the descendants of William continued to speak William’s fusion of French and Norse. Only after eight generations, did a descendant of William, Edward lll, start to speak publicly in the new language. Early Modern English, which had emerged as a new fusion from the various previous fusions.

Edward’s rising star was a young Geoffrey Chaucer. From a young age, Chaucer carried out important official, diplomatic, and financial duties. But he also wrote the Canterbury Tales, setting out the fashions of speech at the time. It was fashionable to speak what Chaucer called ‘French’. But there was a snobbery here. The prestige variety was the language of Paris and the French court. There was less prestige in what would seem to have been a pastiche of the Norman French of older members of the English court. Speech was as much of a cultural minefield in Chaucer’s England as it is today.

The Great English Vowel Shift

In Chaucer’s time English was just starting to undergo what the Danish scholar, Otto Jespersen, called ‘the Great English Vowel Shift’ by which the pronunciations of a number of vowels all moved together. Something similar is happening today in in different parts of the USA. So the process can now be studied comparatively. By this sort of process, a critical number of people all independently start to change the way they say groups of vowels at the same time and in the same way. In North America, the process is being studied by William Labov (1994, 2001). He shows that the process is being led by feisty, thirty-something women, not in visibly-influential positions, but with strong social circles around them. It is a reasonable guess that the leaders of the Great English Vowel Shift were similar.

The changes are slight and not noticed until they have gone through three or four generations of change and one vowel is said just as a completely different vowel was said at the beginning of the process. For example, in Chaucer’s time, the word divine sounded something like DIVEENEH. 200 years later, by the time of Shakespeare and Elizabeth 1, divine had something like its modern pronunciation.

But the spelling was now chaotic. And the chaos has remained.

The little word, do

In Shakespeare’s time, by another major change, people were starting to say “Do you go to church?” as opposed to “Go you to church?” From the time of Chaucer, the speech and the language had changed profoundly.

Rescue?

By the time of Queen Elizabeth l, English had chunks of Old English, Norse, French, Latin, and possibly a Celtic language. Four scholars independently suggested different ways of making the spelling less chaotic. With a monarch, who was herself a significant scholar in her own right, and very interested in language and philosophy, there were some of the conditions for a spelling reform. She followed Alfred in making her own translation of Boethius. But with the state threatened from within and without, the spelling of the language can hardly have seemed like a major political priority. So the scholarly suggestions were ignored. And no major progress has been made in the centuries since.

A quart in a pint pot

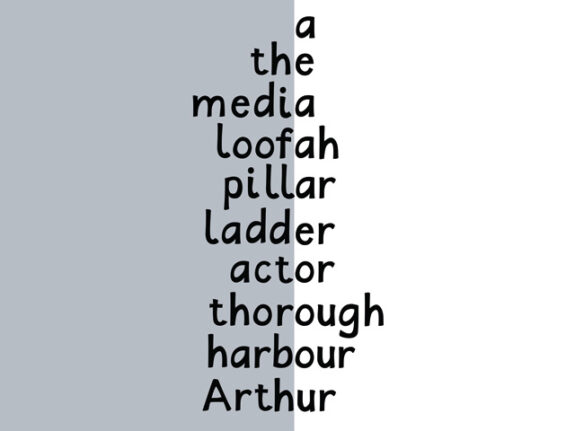

The big problem for English spelling is that English now has almost twice as many speech sounds or ‘phonemes’ as the Latin which provided the letters.

Whereas Latin had five vowels, each with long and short versions, the English sound system has always had six short vowels in hid, head, had, hut, hod and hood, and more long vowels, some of them ‘diphthongs’ – with the tongue rising in mouth in the course of the articulation, all articulated more towards the edge of what is often known as the ‘vowel space’ – with more tension in the tongue.

Other western languages, like French, German, Danish, Poltish, Icelandic, Turkish use special characters or accents to try and squeeze the quart into the pint pot. But not English. The blame can probably be laid at the door of the scriptorium masters of early Norman England. The English scholar, Alcuin, who had laid down the look of the madern written page at the court of Charles the Great, 200 years before, would have been horrified. But the early Norman scriptorium masters would seem to have discounted such opinions.

Logic and keeping up to date

Russians and Icelanders are used to keeping their writing system up to date. But the British protest about the slightest change to even the most illogical of features, like the apostrophe, denoting possession. after the noun and before the S in the kid’s clothes, but not in its, as in ‘the palace and its treasures’.

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk

One rare example of a writing system being successfully reformed from top to bottom was in Turkey in 1928. Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, followed a suggestion which had been in the air for some time to replace the Arabic script from the time of the Ottomans with something more suitable. Turkish has eight vowels contrasting with one another, but only four in any one word, in contrast to Arabic with only three vowels. So Arabic script is not well suited to represent Turkish. Atatürk asked how long the task would take. He was told (not unreasonably) about five years. He said: Do it in three months. An astonishingly good job was made of the task.

Visible speech

Alexander Melville Bell proposed a completely new writing system in 1867. He called it ‘Visible speech’, and he put it to the government of the day, with the explicit aim of promoting international understanding. As a Scot, he was particularly aware of the suffering of wounded Scottish soldiers who had born the brunt of much of the fighting in the Crimean war. Visible Speech was the first step towards a phonetic alphabet. But unlike the phonetic alphabet, devised in the 1890s Visible Speech was deliberately based on what are now known as ‘distinctive features’, rather than what Bell contemptuously dismissed as ‘Romic’ characters. Bell’s suggestion was ignored by the government of the day. But while Bell made some significant advances, like recognising the important contribution of the lips in the vowels in hoot, foot, paw, and pot, his feature system has not stood the test of time. And various features are still the topic of intense debate. While it is obvious and generally agreed that the positioning of the tongue is critical, much of the debate is about finding a system that works for every known language. And Visible Speech is now just a footnote in the history of writing and the theoretical study of speech.

Being in the right place at the right time

The only time it seems to be possible to carry out a successful root and branch reform of a spelling system seems to be in the course of a global transformation of society and with the support of those leading it, as by the Russian revolution and Atatürk.