Proposal / Hypothesis

Evolution and acquisition

A specific and unique sensitivity

The evolution and the acquisition of language

Subjects and data

Steps

-

-

Lexicon

-

Greetings

-

Statements and headship

-

Question

-

Projection

-

The probe–goal relation

-

Complementiser and Phase

-

Binary branching

Implications

Precursor cognitions and conclusion

A specific and unique sensitivity

For the overwhelming majority of humans, in the first months of life, a special sensitivity starts to develop, a sensitivity which has no equivalent in any non-human species. The baby starts learning to talk. This sensitivity lasts throughout childhood, but normally not beyond childhood. That much is obvious, widely agreed, beyond dispute. But by the proposal here, the way speech and language work and the way they are learnt by children are a direct reflection of the way they evolved in the human species. There is clear empirical data. But the reasoning may seem dense. I can only apologise.

The sensitivity here defines both an infinite capacity and significant commonalities across all members of the human species, irrespective of the language that is spoken in some particular group, no matter whether it is numbered in the thousands or in the millions. The Faculty of Language or FL is plainly not expressed at birth, but it develops throughout childhood by ‘acquisition‘. Children are expected to master this infinity and commonality without any special help or instruction, other than on words which they may hear said, but they should not use themselves. The fact that acquisition is possible is known as ‘learnability‘. Of course, the functionality here is sometimes impaired. Hence this website.

There are two big differences between modern acquisiton and the historical evolution of the functionality. What the neonate inherits is a copy of the fully evolved Universal Grammar, UG, as the basis of FL. And what the baby and small child hears is a partial espression of the grammar from competent adult speakers, even though much of what is heard is in bits and pieces as the speakers change their minds about what they are trying to say. Even if the child never hears anything but perfectly formed sentences, what he or she happens to hear said is essentially random. But the end result is a well-defined UG. The contrast between the randomness of children’s experiences and the generality of the end-state is often referred to as the logical problem of language acquisition.

As David Adger (2019) points out, the child is soon able to say and understand things which, almost certainly, have never been said before in the whole course of human history.

Following an analysis due to Noam Chomsky (2000) and work by him and many others since then, I assume here that UG and FL are strictly human specific, by an inheritance, expressed partly by the human genome and partly by human experience. For the sake of learnability and for many other reasons, acquisition needs to be broken down into its simplest possible elements, some specifically linguistic, and others defined by general cognition.

By a hypothesis here, Acquisiton Recapitulates Evolution, ARE, I propose here that:

- By ARE, the specifically linguistic elements evolved by at least seven steps or saltations, each one simple, but of great subtlety and of the most enormous significance for humans and their language, as exactly reflected in children’s acquisition, albeit on a time scale of days and months, as opposed to tens or hundreds of thousands of years for evolution;

- The distinctive character of ARE, reflected in every step, involves a relation which I call ‘Geometrical Merge’ involving sets of two vectors originating at given points, each vector of some defined length and angle.

- But like any other natural process, acquisition can go wrong, either due to a biological error, or by some human disruption, such as long term seclusion, as forced by Covid regulations in 2020.

The hypothesis here has been presented in slightly different versions to two international conferences, in 2022 and 2024. I am currently registering for another PjD to work on it further.

It has a very immediate application. The long term effects of Covid seclusion are only now becoming apparent. For how many and for how long are the effects likely to last? Will those affected just grow out of it? Nobody knows. What I am proposing here bears on the central questions of clinical linguistics. It remains to be seen whether these need to be amended in the light of the Covid evidence.

The properties by the proposed sequence here are abstract. But they are no more abstract than the straightness of the line between footfalls which the child is learning to walk along. The straighter the line the more efficient the gait becomes. More energy is used to propel the body forwards, and less to stay upright. This gait allows humans to run for longer on two legs than faster-running prey on four legs. But few, apart from trainers in athletics, think about the straightness of the footfalls. Abstractness is useful in relation to speech and language, as well as for athletics. When the acquisition process goes wrong, some abstractness can usefully guide the process of clinical investigation. What questions should the clinician ask when? This is what the hypothesis here is about.

Consider the child of three who seems to have just one word. What does this mean? What is the likelihood of the child learning to talk normally? Have the parents done something wrong? Is the child likely to grow into an adult with a ‘communication problem’? Is there a way of reducing the chances of this? What can be done to help? To answer such questions, it is worth sharpening our understanding of FL and UG and, I submit, their possible evolution.

The evolution and the acquisition of language

Why ask about evolution? There are now many proposals about the evolution of speech and language. But in 1866, the Linguistic Society of Paris banned all discussion of the topic. There may have been a suspicion that research would point towards an African origin of human language, undermining the assumption by most Western intellectuals at the time of white European superiority. But whatever the motivations of the ban, it held for over 100 years. The first breach of the ban was by Eric Lenneberg in Biological Foundations of Language (1967) with an appendix by Noam Chomsky. The breach was gradual. But now the evolution of speech and language is the topic of conferences, journals, books, and touched on in movies and novels.

Robert Berwick and Noam Chomsky (2016) propose one decisive step, discussed below, putting two words together, characterising this as ‘Merge’. By the proposal here, the notion of Merge needs to be reformulated as ‘Geometrical Merge’ in order to encompass the first steps, before the notion of words was well-defined when the merging involved not words, but the foundations of words and, separately, the speech sounds with their own internal featural elements, and. in relation to one another, the structure of simple syllables. So by the time the first words evolved, there was already a quite elaborate structure. And in all there was not one step, but at least seven, by ideas from Nunes (2022 and 2024). Necessarily each step was essentially simple, and part of the same evolutionary sequence. In a seemingly paradoxical way, the effect of each step was to reduce the scope of any single process in the building of a linguistic structure, what is now known as a ‘derivation’, This is quite unlike an informal observation of first language accquisition, which seems to be a continual process of advances so small that they cannot be usefully distinguished from one to the next.

By the proposal here, Geometrical Merge is at the centre of the seven step evolutionary and acquisition process. By this reasoning, the acquisition of speech and language by children today and the life long capacity of humans everwhere to learn new words, must exactly follow the original evolutionary sequence. It is reasonable to suppose that the evolutionary sequence was over thousands of generations rather than the days and months of modern acquisition.

This stepwise treatment is motivated by the evidence of language acquisition, and by the evidence of UG. My proposal of a sequence of highly discrete steps departs in significant ways from Chomsky’s ‘Strong Minimalist Thesis’ or SMT, as set out by Chomsky and others (2023). I thus assume that language represents a most useful adaptation, and could not have evolved entirely by means of a single mutation. The aspects of the SMT discarded here are separate from its main empirical thrust. My proposal here thus rests on a vast archive of empirical and theoretical work, almost entirely initiated by Chomsky since his first published work, written in 1949. This 74 year lifetime oeuvre and the archive of technical work which it has inspired form the basis of my proposal.

If acquisition exactly follows evolution, this has a significant bearing on what can usefully be done where the normal acquisition process goes wrong, as biological processes are apt to do. Proposed interventions can be compared in terms of how far they correspond to a plausible evolutionary sequence.

Shigeru Miyagawa and others (2025) propose that the seventh and last of the functionalities proposed here and thus the whole process of modern human language evolution must have been fixated across the ancestral population by around 135,000 years ago. By the proposal here it must have begun much earlier, perhaps around 1.8 million years ago. Steven Mithen (2023) almost suggests as much. Denisovan and Neanderthal humans cannot have enjoyed the fully developed capacity. When they partnered up with modern humans, their speech may have sounded like the speech of a three year old today sounds to modern adults. Relationships would seem likely to have been quite seriously exploitative.

From the study of ancient and modern DNA, it can now be computed that for most of six or seven million years since LUCA, the world population of humans was very small – in the single thousands, with breeding groups often becoming extinct. This is likely to have continued even when human ancestors were decorating the walls of caves with an artistry that impressed Picasso. The surprise is that humans survived at all. It was only when modern techniques and ways of organising society started developing – about ten thousand years ago, that the world human population started growing exponentially.

Going beyond the scope of this proposal, we play with the basis of this complex modern existence at our peril. Cavalier attitudes threaten another extinction, this time of our entire species.

Subjects and data

The subjects here represent the smallest sample for any logically possible generalisation, two. The subjects were the youngest two of my three children, Joe and a younger brother, Frank, both developing normally, from a liberally-minded, middle-class family, interested in books, museums, galleries, history, art and politics. They went to a neighbourhood, non-denominational, local authority school, catering for children from a wide variety of social and ethnic backgrounds. The observations are from diaries kept by my wife and myself over ten years, now amounting to about fifteen thousand observations, filling nine cathedral analysis note books.

We tried to make our observations as accurate as possible, as soon as possible after the event. Obviously we must have missed many developmentally significant occasions. The observations exampled here exhibit commonalities across the two boys. Because of the age difference, it is not plausible that the older of the two was significantly influencing the younger, other than on matters of interest to two small boys. Listening to them talking with their friends and peers there was nothing obviously singular about their speech and language. Generalisations across the two are thus likely to be significant.

It is only coming back to these records for analysis forty years after they were made that it is becoming clear how much they reveal. One cannot listen too carefully to the details and nuances of what children say. They can say more than they seem to on a first listening.

The next stage by the research here will be either to add more subjects or to amend the methodology.

Both speech and language are enormously complex. The first efforts are, by virtue of this rather obvious fact, hard to understand – to the point that it is often hard to decide exactly what is being said. But on this basis, any degree of structure understandable as speech may be intrinsically significant.

Following the convention established by Jean Piaget, ages are given as 0; 11 (10), meaning the tenth day of the eleventh month. For our purposes here, this degree of precision is useful. Some developments happen over a few days, or overnight, or less. In the cases exampled here, the observations were the first cases of utterances satisfying some particular grammatical criterion.

Steps

All of the steps proposed here are given in terms which make no reference to any sort of linguistic category. Ot they could not be encoded in a genome, capable of being transmitted from one generation to the next. The steps are as follows.

1. Lexicon

Any system of communication based on discrete meanings and external symbolisations entails a linking between two unlikenesses, necessarily a strictly binary relation, something that has to be postulated for the alarm calls of many species, what seem to be the naming calls of dolpins, and the much more elaborate communication systems of chimpanzees. But for human language, this relation was defined in a new way, one which allowed it to develop recursively into the elaborate structures of poetry, songs, jokes, irony, words of indefinite length, and legal contracts and political treaties and agreements.

Consider the first words by two children. One child, Joe, at 1; 0 (14), seeing the swings in the playground said something which his mother heard as “See saw” – as DEE DAW, with the consonants as what are known as ‘voiced stops’, stops because the airstream is completely blocked in the mouth, and voiced because the action is only momentary with the buzzing sound from the larynx beginning as soon as the closure is released. The partial closure by S is replaced by complete closure. Joe’s younger brother, Frank, says “Bu” on seeing a bus, with no discernible S, at 0; 11 (10). All of these forms seem to involve the fundamental property of reference, at least to some degree.

Disregarding any possible internal structure, on what might seem to be the simplest possible analysis, BU and DEE DAW are by a simple chaining or ‘concatenation’ of elements, unanalysed consonant vowel, CV, structures, parrot-like mimicries of speech, that there are no grounds for any further analyis:

By such an analysis the mere fact of the expression and the meaning being combined, the first single words are essentially like chimpanzee hoots or whoops, as has often been suggested, more human-like, but in principle no different.

It might seem that it is parsimonious to delay for as long as possible the point at which we postulate any sort of powerful capacity, perhaps until the grammar is generating structures with some degree of complexity, such that the infinite capacity is obvious. But this would be to postulate two pathways, one leading to a finite set of outputs and the other leading to an infinite set. But on the grounds of continuity, the greater parsimony is by a single pathway, a continuity with the rest of the pathway to competent speech and language, respecting the complexity of the child’s first word, whether this is understood as referential, calling up an entity not actually present at the point of the utterance, as by mum, mummy, dad, daddy, cat, pussy, dog, doggy, horse, horsey, bird, birdie, car, bus, lorry, or as a standalone expression of discourse like hello, hi, or goodbye.

But by the proposal here, the first human words are utterly unlike any sort of non-human expression. In evolutionary terms, the human innovation was to evolve a new sort of relation between the unlikenesses, where the relation is itself part of the definition. Each relation to each element is by a vector, defined only on its length and direction. Each relation has to be in a plane defined by the vectors. This applies to the relation of unlikeness between the the meaning and the externalisation. In the modern child’s first words, the externalisation may involve the reduced resonance of the initial consonant, and the highly-filtered resonance of the vowel, defining the phonetics of the expression, as sketched below. The first step in this process was and is to reduce the external elements of the expression to their simplest, logically possible, perceptibly distinct forms, contrasting sorts of featural element, and then to revere the decomposition, recombining elements for the sake of clear articulation. The fact that the relations are by vectors allows the stages of decomposition and recomposition to be accurately tracked. This is diagrammed below in terms of two abstract features, feature a and feature b, taking the form of any parts of the vocal tract (or the body, if the language is by sign). For the sake of simplicity in the diagram I suggest only vocal tract gestures. For features a and b, non-vocal gestures, movements of the hands and fingers, settings of the head, movements of the eyes, could be freely substituted. The human expression sits on a highly elaborated foundation.

What makes this different from a chimpanzee’s hoot or shriek or warble is the double branching. The novelty of the step involved both branchings. The recomposition gives their assembly into some prototypical part of a phoneme or speech sound. But primordially and in modern children’s early speech and language development, the recomposition may be uncertain or not fully defined. So there is no reason to expect that primordial expressions sounded like modern EE, AH, TOO, COO, DEE or DAW by modern phonemic or syllabic structure. Modern chimpanzees’ apparent inability to copy human speech tells its own story. Primordial articulations may have been different in any number of ways, in all probability using features that could be drawn from an existing system of shrieks, hoots, grunts, or howls.

By virtue of the double branching, as by the diagram above, the first human language was different from any sort of alarm calls of vervet monkeys or prairie dogs, or the richer but seemingly less specific systems of chimpanzees, or the marking of individual and group identity by dolphins.

In evolution, the physical aspect may have been either gestural or vocal. The proposal here is neutral on this point. If primordially there was a bias towards physical gesture, this bias must have disappeared as language evolution progressed, or there would be sign languages used natively by normally-hearing populations, without the encouragement of a significant proportion of the population born deaf. Mike Tomasello (2020) argues for a gestural origin. But babbling seems to be something most human infants do whether they can hear or not, even though deaf children babble only for a short period. This seems to me to bias the probabilities in favour of a the primordial language being vocal.

As a prelude to speech, babbling addresses just the external aspect of language.

By the proposal here, from the very beginning, the externalisations had separate elements, the prototypes of modern features or the simplest sort of modern syllables, known as CV or consonant vowel syllables, widely thought to occur in every language. If (improbably) CV syllables were primordial the contrast between the two elements may have been with respect to the greater openness or sonority or resonance of vowels. More probably, the first step on the pathway to modern speech and language, the initial prototype, is not likely to have differed greatly from ape-like hoots as a result of the new process. But there must have been a perceptible difference in order for the evolutionary novelty to spread. It is reasonable to suppose that the fitness advantage of this more complex arrangement was that it enabled speakers to effect their gestures more accurately, to focus on their effect, and to classify them in a prototype dictionary, a lexicon of comparable items, differentiating features more narrowly and more precisely.

The two notions, of Decompose and compose, are also invoked by Matilde Marcolli (2023), to explain two aspects of Merge, described below. By the proposal here, Decompose and compose should be seen as the basis of the process by which linguistic atoms are put together to form the basis of the lexicon. It is both primordial and the first step on the modern acquisition pathway.

By a strictly continuous, feature-based analysis, the first word is not just more sophisticated than a hoot. It is something else entirely. A featural analysis is more plausible than an apparently simpler concatenation. There is a double branching. Even with only a small subset of the features by fully competent speech, the features can be cross-multiplied in various ways, allowing the lexicon to be expanded, and forms to be extracted at will.

On a completely different time scale from modern acquisition, the lexicon could grow exponentially. One form could be compared with another. New forms could be added, each distinctively represented by branched structures, to be articulated and understood accordingly.

Both by evolution and by the fully evolved modern system, such a ‘lexicon’, or store of words or signs, could be freely supplemented throughout life. Lexical items are thus quite different from any shriek or howl in response to some situation.

The relation between physical and semantic features and the classification of entries in a lexicon are common to all naturally spoken, modern languages. This breakpoint between human and chimpanzee-style communication cannot have been by a gradual transition, but by a reconfiguration of the relation between the two sorts of feature. This reconfiguration was the evolutionary cognitive genius. Without the decomposition and recomposition, there is no way that the primordial hoots and shrieks could have evolved into what they became.

Anna Maria di Sciullo and Edwin Williams (1987) suggest that the lexicon is a place of lawlessness and unpredictability. But by the phonology and the combination of different underspecification theories proposed here, by the next but one step to be proposed here, defining what Chomsky and numerous others characterise as Merge – as an irreducibly necessary aspect of human language, the keys to the cells of the lexicon are strictly organised. They are highly compacted. Although the principles of this are common to all languages, the detailed implementation is language-specific, different for every language, necessarily within the child’s learnability space. Nunes (2002) shows that this learning is still normally still in progress at the age of eight, at least for the hardest words.

The principle of compacting is plainly not learnt. It has to be available to the child from day one. It has to have evolved to be able to work the way it does. This evolution cannot be an aspect of human culture or it would vary from culture to culture. It has to be biological. Hence the current notion of ‘Biolinguistics‘.

If the proposal here is on the right lines, Lexicon defines the beginning of a human-specific pathway

How far the first inventor or inventors were CONSCIOUSLY aware of what they had ‘invented’ is obviously impossible to say. But it seems reasonable to speculate that even just one suitable expression could be very appealing, that there was a selective advantage. More mental investment in the form may have allowed more attention to other aspects of the expression. The adaptation here wouold seem likely to have conferred a degree of advantageous fitness. Inheritors had a greater chance of mating and thus of passing the adaptation on. All we know is that it was noticed. Or it could not have spread.

Even if the first word or syllable is imprecisely articulated and hard to even identify, it still has some rudimentary structure, typically with an initial consonant followed by some sort of vowel. There may be even a vestige of a less highly stressed second syllable. Semantically, this may be referential or based entirely on discourse. Significantly there are only a handful of discourse expressions in contrast to those entering the system of meaningful combinations, known as syntax. Reference is universal across languages, allowing an entity to be called up just because it happens to be in a speaker’s mind.

By the framework here, it is likely that both primordially and in modern acquisition, definitions were and are imprecise, making the speech is hard to understand. The structure (or lack of it) is both primordial and characteristic of early development.

Modern language exploits the complete resources of a system which is continually changing in how things are pronounced, in how words are put together, in what they mean, and so on. But that being said, it is now in a sense fully evolved. The primordial system has been supplanted by both evolution and what is known as ‘grammaticalisation’, the churning over of the grammatical apparatus under various pressures over tens of thousands of years, some pulling in opposite directions.

There are fossils of the primordial sound / meaning relation, as expressed by the modern lexicon, in:

- The lexicon itself;

- The sending of information of two sorts to two quite different sorts of interface, both conceptually necessary, represented in primordial human expression, and as significant in modern speech and language as at the point of evolution;

- The long period in normal language acquisition, of anything between two and six months, of just single words;

- English yes and no and what are known as ‘modal particles’ or ‘discourse markers’ including Ah for pleased surprise, Eh as a query, tut tut for disapproval, hello, bye bye, curses, and so on;

- Expressions like sh as a call for silence;

- What are known as ‘imperatives’, commonly, as in English by the ‘root’ form of a word, such as come and go, sometimes for the sake of saving life;

- Expressions like “genius” or “rubbish” in response to a performance.

The single words of modern one year olds are unlike the primordial forms proposed here in that they exploit combinations of features by later steps. But they are used in a way characteristic of the primordial system.

2. Greetings

Greetings signal a personal relation between people in a particular sort of situation according to their familiarity and respect for one another. For small children, they just signal a momentary relation. But the mere fact that they occur so early in the acquisition process signals the importance of respect, which children may be starting to learn about from around three – much later than they start learning about syntax.

By the first greetings, there is a reduction of the number of elements involved by pairing the simplest sort of element such as a standalone , discourse expression’, such as bye-bye, with a reference to some animate entity, a prototypical syntactic object. The contrast is between elements such that one relates only to the discourse itself and the other is a prototype of what will become an element of syntax, including nouns.

Joe at 1; 5; (23), six months after his first ‘words’, said “Bye, doggy”.

Frank at 1; 2 (22) said “Bye bye, Daddy”.

Bye or bye bye are clearly aspects of discourse, as are ah, ey, uh, oh in adult language. Doggy, addressed to a toy dog, and Daddy, are seemingly referential. So there is discourse and reference, but with no internal structure other than the contrast.

This primordial system is reflected in modern language in at least two ways:

- Expressions standardly by root forms combined in ways falling outside the terms of the grammar, kill joy, go between, go slow and so on, noted by Ljiljana Progovac (2015);

- Possibly at least some adverbs, as the only sort of word which can appear in different positions in English, albeit with some subtle changes in meaning, as with sadly in any of all logically possible positions in “Sadly, he is going to die”, “He sadly is going to die”, “He is sadly going to die”, “He is going sadly to die”, “He is going to sadly die”, “He is going to die sadly” – all grammatical, at least for those who allow infinitives to be split;

The modern infant generally puts his or her first two ‘words’ together around the point when the vocabulary reaches around fifty items. There is no reason for assuming that Recognise and address evolved at the point when some particular number of items became accessible, but it is clearly possible that in evolution Recognise and address was triggered by the growth of the lexicon.

3. Statements and headship

Many of the first statements as just observations about the world, as it appears to the child, rather than expressions of need or desire.

Irrespective of their purpose, in these first statements, there is a further restriction of the number of elements in the computation by limiting them to different types, as some sort of prototypical categories, with one becoming the head of a combined expression. By the notion of ‘Geometrical Merge’, the different roles of the elements are defined by their respective lengths and angles.

For example, Frank at 1; 3 (2) said “Open door”, and Joe at 1;7 (30) said “In er car…. In car”. By the analysis of Chomsky (1995), this is by the ‘merging’ of two “formatives’, in these cases with open or in becoming the head of the merged expression.

In these examples, only one element is referential. The other is a prototype of some sort of syntactic object, in these two cases a verb and a preposition, although not yet with such a categorisation well-defined. Crucially, neither is such that it can stand on its own. Discourse elements are thus excluded. A headed structure can’t include bye bye or hello.

When the phrases “In car” and “Open door” were uttered it seemed probable what they meant, but not certain. The relation is asymmetric between two contrasting elements. But however they should be understood, both of these phrases have well defined heads, in and open, contrasting with the clearly referential elements in car and door. In the framework here, the non-head is known as the ‘complement’. By the diagram above, dominance is thus built into the system.

The head of a structure can merge with another structure, allowing subjects to be formed in the same way.

By a very general relation across the grammars of human languages, not just English, phrases have heads with complements, and heads have specifiers. The subjects of sentences are prototypical specifiers. Between the elements of any branching there is a sisterhood relation.

At 1; 3 (2) Frank says something lile “ER want that”, with a non-specific vowel sound, shown as ER, rather than a clear I. But it is in the appropriate position in the structure to be understood as I. At 1; 8 (22) Joe says “All gone”.

- With the branching applying to just two elements, sisters in the framework here, headship is thus essentially a relation between prototype syntactic elements, both with parts. In the modern child’s process of acquisition, by the simplest interpretation, “In car” involves two elements, car, essentially noun-like, and in, as a step towards a preposition. “Open door” contrasts noun-like door and verb like open. Structures, with what traditional grammar calls ‘subjects’ , can be expressed on noun-like elements. Thus the abstract (Er) element, noticed in the speech of many children expresses a purely grammatical or syntactic subject role, a seemingly universal property of sentences.

- What are known as ‘thematic roles’, including agency, ownership, location, benefit, destination, or experience, can be expressed;

- External Merge signals the first step towards distinctive ‘parts of speech’ as these are called by traditional grammar, nouns like car, Mummy, Daddy, verbs like want and like, prepositions like in. The items become differentiated, as the only sorts of expression on which grammatical operations can be defined. On the simplest plausible readings, open and in are plainly heads. Both elements can now express formal relations, as head and complement, to the expression as a whole. There is a grammatical relation between them, each with an an irreducibly necessary, structural role. But it seems premature to regard such elements as fully-defined nouns, verbs and propositions;

- The elements have features which define the interaction, as opposed to some purely accidental relation, as by ooh, eh, ah, yes, hello, good bye,and so on, all independent from the grammar because they can stand on their own, sometimes adjoined to it, but not by External merge;

- By virtue of the headship role of one element by each branching, and developing an idea from Nunes (2002), it is possible to combine different sorts of ‘underspecification‘, reducing the lexical storage to the minimum, expanding it only for purpose of clear pronunciation.

4. Question

There are many ways of signalling curiosity, by a tone of voice or a raised eyebrow. The most explicit way is by syntax, defining what sort of information the questioner wants to know. But the syntax has to be formed. Of course, the wanting-to-know can then be turned on its head, in irony or for some other reason.

In modern acquisition, soon after two words are put together, a question is asked or answered involving a question word relating to one of the items in the two word combination, particularly what, where, and so on, signalling points of curiosity, as a key factor in discourse.

English syntax forms a question by reversing the order of the subject of a sentence and the signal of time, known as ‘tense’. This involves a tense-carrying element of the verb phrase, using a form of do if tense is embedded in the verb itself, as in the simplest case. By the profound insight of Chomsky (1957), the marking of tense is separate from the verb itself. Hence “Did you say that?” “I did”. The force of the question in “Where are you going?” determines a reversal of the sequence of you and are from the sequence which would be followed in the response statement “You are going to the shops” or I and am in “I am going to the shops”. Questions beginning with words like where (or their equivalents in most languages other than English) are asked with where mostly on the left of the structure, as in “Where are you going?” In a full-sentence answer, the requested information is on the right, as in “I’m going to the shops.” Words like where appear to move leftwards. But rather than actually moving, they are fished, as it were, from inside already completed structure. This fishing involves a distinctive length and angle in the vector involved, marking what John Langshaw Austin (1962) called the ‘‘illocutionary force‘ of a structure, as a statement, question, entreaty, and so on, in a way separate from its propositional content. In “What did you say?” the word, what, and the whole sentence are different sorts of syntactic object, with what having a special status in relation to the illocutionary act. The ‘force’ of a question is an effect of the geometry of the structure and the circumstances in which it is uttered.

Building on the functionalities by the three previous steps, by a further restriction on the set of elements at play at any given point in the derivation, by an analysis originally proposed by Chomsky (2004), the merging is now from an array of previously selected lexical entries. From this array, it is then possible to extract a particular, suitable item. An item is ‘internally merged’. This further reduces the set of elements in play at any given point in the derivation.

Typically, as in English, an internally merged item, B in the diagram below, is then not pronounced at its point of origin, shown in grey below.

For example, at 1; 4 (27) Frank is asked, “Who wants some chips?” And he replies “Me”. And at 1; 5 (9) he asks “Where chicken?” Both the appropriate answer to a who question and the where question 12 days later suggest a grammar capable of making two uses of the same element, once to define an identity or location, and then, by Internal Merge, with the force of a question.

Joe at 1;10 (3), says “Daddy upstairs” where Daddy seems to be the ‘subject’ in traditional terminology, and at 1; 10 (27) “Where Daddy?” with where seeming to define a clear question. In the declarative “Daddy upstairs”, both element are only extracted once. But in the question “Where Daddy” it is extracted with a notion of location, and then extracted once again with the force of a question. In other words, where is pronounced on the left of the structure, and interpreted on the right , where it is left unpronounced.

Here where is fulfilling a special, questioning role in the structure, by the framework here, a universal role.

At this point in the development of the child’s grammar there is no evidence of any category corresponding to ‘Tense’, as by the difference between do and did. All we have evidence for is an interpretation of an element pronounced in a different position from where it originated, as shown by the green arrows.

By this step:

- Elements of composed structure can be recomposed at a higher level;

- The cognitive load of searching for and extracting items from the lexicon is greatly reduced. At this point in language acquisition, the lexicon is expanding rapidly. Simplifying the task of searching for and extracting a word is thus a valuable increase in fitness. This is easily and obviously detectable because questions are now defined by the ordering of elements, although not yet by any overt expression of Tense. Questions with a Wh word can be asked or understood.

Significantly, English also allows forms like “Daddy is where” or “The chicken is where”, typically with where heavily stressed, no longer with the force of a question, but as statements of surprise or astonishment.

5. Projection

Questions are not fully-defined, at least in English, by the leftmost positioning of a Wh element. For clearer understanding, there needs to be some evidence of the pivotal, inflected element, which I shall call simply ‘Projection’. The simplest case involves a relation to the immediate present, defined not on the verb itself, but on a higher position on the ‘spine’ – what was traditionally and in earlier versions of the framework here as the ‘auxiliary’. In relation to existence or situation, the inflected form of Be is expressed by the word is or its contracted form, written as ‘s.

While Question extracts elements from a work space, Projection projects them upwards – necessarily because that is the only possible direction.

Projected elements, known as ‘functors’, are only definable by their relation to another element within the structure or to the structure itself. Functors are marked in English in obvious ways, easily detected by the child learner. Their sound structure can be reduced, by changing or losing their vowel, or by losing one of the consonants.

Frank at 1; 5 (29) asks: “What is that?” His mother, who made the observation, noted that the is form was clearly articulated. Joe at 1;11 (12) asks “Who’s that?” On the same day, looking at a picture book together, his mother asks: “Where’s the bus?” Joe replies: “There’s bus.” At 1;11 (14) he asks: “Where’s man tractor?”. It was not clear whether he meant “Where is the man’s tractor?” or “Where is the man for the tractor?” or something else. The point here is the articulation of the ‘s form, as a contracted form of is. These are the first uses of an is or contracted ‘s form by these children. Here an element is inserted into the structure and anchored to the here and now of the utterance, reflecting an aspect of the discourse. The functor here does double duty, marking both the relation to the present and the fact that the question is about a single entity. The fact that it is expressed by a contraction makes it highly visible and thus easy to identify and learn.

Showing the new functional projection in quotes, it is projected to a point in the structure where it is the sister of the question form, here what, who, where.

There is no reason for thinking that there is any contrastive intent here. The child is not also asking things like “What was that?” The ‘S or is just defines an abstract projection, albeit one with a highly significant formal role. In a broader sense, the form signals the accessibility of elements which are purely functional, with their own corresponding projections.

6. The probe-goal relation

The sixth step defines a way of measuring and comparing degrees of dominance by what is known as the ‘Probe Goal’ relation. Indirectly, as part of a larger package, questions are thus now more fully defined. Where any two branchings imply a corresponding contrast in degrees of dominance, by this sixth step, a probe ‘looks for’ a structurally close goal. The scope of operations, each doing just one thing at a time, is restricted by comparing and measuring degrees of dominance. The relation characterises numerous phenomena in the grammar. In English it applies to a seemingly disparate set of functionalities:

- Successions of verbs as by want to go, where want ranks above go in the structure. Verbs like want are known as ‘control verbs’ because they control the tense, person and number, i.e. all the variable features of the lower ranked verb;

- Complexity in ‘noun phrases’ defining possession and qualities, as in Morph’s box and more that in “I need more that”;

- What is known as ‘Case’, expressed by the difference between he and him, she and her, as ‘arguments’ in one of various relationships, essentially who is doing what to who, but changing as roles change or speakers take turns to talk in pronouns such as I, you, he and she, expressing the special role of the ‘subject’ of the sentence;

- What are known as ‘reflexives’, as in “I hurt myself”;

- ‘Agreement’ between a nominative subject and the form of a verbal element expressing tense, as between I and am, or its contracted form ‘m.

- What are known as ‘passive’ forms such as broken, where the theme or patient of an action comes to dominate not just the verb, but also in English an auxiliary form, such as is.

- Negatives by not and its reduced form written as ‘nt, where the negative form only appears immediately after the form expressing the tense in doesn’t, didn’t, can’t, won’t, and so on.

In many cases, more than one of these phenomena are manifested in the same utterance.

At this point in their development, in terms of their chronological age, Frank, the younger of the two, was some months ahead of Joe.

At 1; 11 (1) Frank said “Want sit lap” with two root forms of the verbs, want and sit. At 2; 3 (26), Joe said “Want help daddy” where it seemed that he wanted to help his father. In Frank’s case want and sit, in Joe’s case, want and help were separate verbs, one at a higher position in the structure than the other. Want is known as a ‘control verb’ in as much as it controls the tense, number, and person of the lower ranked verb, in these cases help and sit.

At 1; 9 (22) Frank said “I hurt self’”, meaning I hurt myself, with I and self with the same reference, with the reflexive self-form one level down from what is known as its ‘antecedent’ – in this case I. And at 1; 10 (27) he said “I found this” with the ‘nominative pronoun’ I next to the past tense found. At 2; 5 (5) Joe said “doggy licking hisself” with the self form picking up the third person of the antecedent.

At 1; 11 (3) Frank says “Baby is hit”, and at 2; 4 (11) Joe says: “Morph’s box is broken”. In both cases the patient or theme, baby in the one case, Morph’s box on the other, dominates two verbal elements, is and hit or broken, one dominating the other, rather than being dominated by s single verbal element.

At 1; 11 (4) Frank said “I don’t like it” with the negative n’t next to the auxiliary do. At 2; 4 (26) Joe said “Mog doesn’t like that”.

At 1; 11 (13) Frank said “I’m making lorry” with ‘agreement’ between the first person pronoun 1 and the auxiliary am. Joe at 2; 5 (7) said “I saw lorry pulling car” and on 2; 5 (11) “I took picture of milkman”. In both of these cases there is significant embedded structure, a clause in ‘lorry pulling car’ and a noun dominating another noun in the substructure of ‘picture of milkman’. In all three cases tense and the nominative case defining the subject role are overtly represented in a sisterhood relation. In Joe’s “I eated that chocolate” at 2; 5 (6), the tense in the verb is manifest in the mistake in eated.

There is the same specifier / head relationship between I and am and between she and is, one denoting the nominative case of the subject and the other denoting the most immediate aspect of the here and now in the discourse. In most languages including English, the key aspect of the here and how is related to time, represented as the tense of the verb, as in the differences between I am and I was and I have and I had. Nominative case is almost enirely grammatical, with no general relation to the needs of communication or the factuality of the here and now. This is disguised by the fact that the subjects of sentences often encode the thematic role of agency, as in “I’m making a lorry”. There is no agency in needing something, as in “I need more of that”.

For both children, there is the same relationship between the elements of a complex noun phrase, such as Frank’s more (of) that at 2; 0 (20), Joe’s lorry pulling car at and picture of milkman.

The expression of these levels of the hierarchy, for noun and verb like elements, varies from language to language. These are things the language learner has to learn. They fall within the learnability space. But the way it works in English is complex and hard to learn. Applied to the output of one another, the set of relations defined so far can be exploited indefinitely. Such a grammar strains both processing and production. It may not be completely learned under the condition of finite learnability. There may have been wide variations in the mastery of the grammar, as in all other areas of human skill from musicality to art.

7. Complementiser and Phase

By this final step, an element, to be known as ‘Complementiser’, is introduced with the effect of completing the derivation, merging with the current structure by the general principle that this applies to just these two elements, itself and the current structure. As the topmost element of the structure, the complementiser defines the force of the structure as a whole. In this way, the grammatical apparatus is factored into narrowly-defined phases, further reducing what is at play at any point in the derivation, but allowing sentences to be of any complexity.

This follows a consistent approach from Chomsky’s first widely circulated (1957) work, proposing a distinction between two sorts of rule, ‘phrase structure rules’ introducing the ‘content’ elements in propositional form, and ‘transformations’ manipulating those elements for the purposes of what John Langhaw Austin (1962) would call ‘illocutionary force’, including questioning and denial. In 1965 Chomsky proposed a division between deep structure and surface structure, with the transformations happening between them, and the rules applying in cycles. In 1986 he proposed the notion of ‘barriers’ with respect to what was at the time considered to be the ‘movement’ of elements such as what and where. Then in 2001 he proposed that information is ‘spelt out’ to two minimally necessary interfaces, defining the meaning and the external pronunciation, in separate ‘Phases’. This is still an idea in the process of intense development and debate, with many different understandings.

By the understanding here, from the perspective of acquisition, but taking also taking account of evolutionary plausibility, each phase has two main aspects, the first comprising the referential and propositional content of a structure, defining the extent to which something is true, false or implicit, the second defining the illocutionary force of statements, commands, questions, pleas, and so on, possibly contradicting the proposition in jest or irony. Discourse features significantly in this second aspect.

A phase is defined by the fact that as soon as it has been completed, most of its structure becomes inaccessible to the ongoing process of derivation. A phase may by expressed by only one word. But it can have a special analytic status, as in the case of the Wh words. As by the primordial step, decomposing and recomposing the elements of the lexicon, the information that is sent to the two interfaces (for physical expression and understanding) has to be detailed and complete.

The novelty, by a phased approach to syntax, is that the factoring into phases can be repeated. The phases are accessible to small children and plausible at an evolutionary level. Both in the evolution of language and in the acquisition of language by modern children, the factoring of the grammar by phases is (necessarily) ordered last.

Here I show accessible elements in bold red, and with a lower, earlier, inaccessible elements lighter.

By this seventh step, the notion of force is expressed as ‘Complementiser’ or C, as the topmost level of the spine, and replacing the traditional notion of a ‘sentence’. Complementisers comprise a small set of words, including the Wh words like who and what, but also words like for in “For Daddy to put on your shoes would be a bit difficult” or that in “That your feet have grown is obvious”. Not part of child language in these cases but necessarily on the pathway to full competence. In simple, declarative main clauses, C is not expressed in English. But it is the destination or landing site of words like what, where and when and expressions with which in questions seeking particular items of information. So C provides a hosting for what in expressions like “What did you say you thought I said?” with what as the complement of I said at the opposite end of the structure. By the 1997 proposal of Luigi Rizzi, the ‘force’ of the structure is expressed as a property of C. This applies no matter whether the structure is a statement or a question, or whether the agency of the subject is diminished by passivisation or in some other way.

The critical evidence for this seventh and final step seems to be those cases where a word like what is used as part of a statement – or ‘declarative’ – but without the force of a true question. These are minimally structures with two clauses, typically the first with a ‘mental’ verb like think, know, wonder, remember. Some information might be given in response. But it is not being actually requested. The child becomes able to develop the structure of a simple question by the fifth step with a word like what on the left edge and an auxiliary form with tense overtly marked immediately after it into a statement about knowing or wondering. I illustrate this with the first two clause instances from Joe and Frank, with the topmost part of the structure with a simple red and black triangle. The structure relevant to the seventh step is in what comes next.

By characterising the topmost level as C, shown here in red. every level from the bottom of the structure to the top is defined in the same way, rather than by giving the sentence a special status of its own.

A mere six weeks after “I don’t know what you want, teddy”, at 2; 9 (28) Joe produces his first sentence with the embedding repeated in “I want to stand on the chair to see what’s happening”.

The other child, Frank, up until this point, the more precocious of the two, now, at 2; 10 (21), says “I want to sit where Joe’s been sitting.”

Crucially, there is no search for information here. Simplifying slightly:

Looking at the two children together, almost identical, sentences with multiple embeddings, accidentally or otherwise, with full grammaticality. The exactness of the similarity between two utterances in two children two and half years apart, only noticed forty years later, would seem to suggest that there is significance in such structures with a Wh word specifying an embedded clause, and not forming a question.

For both children, one aspect of this step is the emergence of questions with when, how, and why, with correspondingly more complex structures on the right edge. But the fact that the commonality across the two is stronger and clearer with respect to the two clause, non-question forms, suggests that the driving here is from the phase structure rather than the obviously important differences between when, how, and why questions with clear question force in a single clause.

As by the examples above, Phase allows the derivation to proceed in steps, as by the process of evolution. But the full application of the principle here takes years to learn. At 9; 9 (13) Joe said “We don’t know whether I’m going to be picked up by who” (of the rather complicated child care arrangements we had in place at the time to allow me to go to a university 70 miles away one day a week). Joe’s sentence is anomalous in as much as who seeks particular information and whether seeks only a truth value. But the structure of two Wh words in the same clause calls up the Phase functionality in a significant way.

By this seventh step:

- Building the derivation in phases allows clause structure to develop, while at the same time limiting how much of the derivation can be manipulated at any one point, reducing to the minimum both Search and the speaker’s and language learner’s tasks in constructing a derivation, allowing complexity to be distributed across it;

- No matter whether Wh words like where and what are used in questions like “What do you want?” or as introducing an embedded clause in a statement like “I know what you want”, they are crucial to the system of Phase, the last step in the evolution and development of Universal Grammar.

- Information is sent bit by bit to the articulatory system to be pronounced and to the semantic / conceptual system for the meaning to be analysed. English marks the point of sending articulatory information much earlier than ‘agglutinative’ languages like Turkish, and many others, with what seem to the speaker of a language like English to be hugely-complex ‘words‘. So this point necessarily falls within the learnability space;

- Hypothetically it is Phase which makes speech and language finitely learnable, at least for the overwhelming majority, giving humans a unique capacity among all species alive on the planet;

- A commonly shared competence can be assumed across the whole population – a huge advantage for a small and highly vulnerable species, as humans were until this point in human evolution. At least two bottlenecks in ancestral populations have been identified from the DNA evidence, with humans almost going extinct;

- Metalinguistic awareness is brought into being;

- Fantasy, fiction, non-fiction, irony, fun, comedy, contracts, all become parts of everyday life.

By the estimate of Shigeru Miyagawa and others (2025), modern levels of competence seem to have become fixated across the population by around 135,000 years ago. The enhanced cooperation by Phase may thus have saved modern humans from extinction. The first step, allowing a prototype lexicon to start developing, must have been correspondingly much earlier.

By the Miyagawa result, it is inconceivable that Neanderthal humans, having separated from the homo sapiens stem at least 500,000 years earlier, had a grammar with Phase. If Joe and Frank’s language development was representative, as it seemed to be to friends, family, and professionals, Neanderthal language would have been stuck at the level of a modern child of between two and a half and two and three quarters. This would have made it very difficult to talk about truth, causality, probability, and moral imperatives. As adults they would be able to understand simple instructions and make simple declarations and observations of fact, but crucially no more. The sticking point would have been at the level of the genome. No amount of loving help and coaching could help bridge the gap. Modern humans and Neanderthals could partner up, have babies, and the babies could grow up and have children of their own, with some inheriting the capacity for Phase, and others not. Given the obvious advantages of the Phase inheritance, it is not surprising that in the long term it was only this inheritance which endured.

Binary branching

Given the simple principle of binary branching, in relation to the phonology of phonemes, English just happens to pursue this branchedness further than most languages. But some languages, including Polish and Georgian, go further. All of this falls within the learnability space, and is often problematic in children’s speech development.

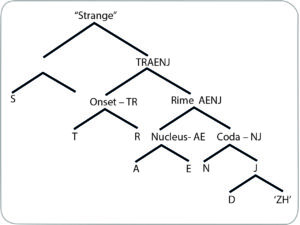

The tree can just develop, adding branches, up to some limit, as by the structure in strange. Here the long vowel is shown as AE, where the two elements are separated in the spelling. The final GE by the spelling is shown as a single J, representing the fact that this is just one sound. But it is also a sound with two halves, known as an ‘affricate’, beginning with a complete closure, shown here with a D, and ending with a fractional release of the closure, shown here as ZH, like the sound at the end of beige and rouge. Respecting the binary branching, the initial S is shown as a dependent off the left edge of the syllable.

Implications

- Pathway. There is an evolutionary pathway from the first human words to the competence needed to explain to an apprentice some skill (such as flint knapping) and a corresponding developmental pathway from the modern child’s first words to his or her fully-mature, adult speaker’s competence ten or so years later. The evidence here confirms Darwin’s hunch that modern humans share a common ancestor with African apes. By a general consensus, the evidence of DNA shows human ancestors diverging from chimpanzees at some point between six and seven million years ago. I assume here that at the point when the two ancestral populations diverged, they shared a system of communication essentially similar to that of modern chimpanzees. Some chimpanzee calls, like the shriek of pain as an individual is attacked vary in intensity according to the severity of the attack, and crucially, are understood that way by other chimpanzees. But an infinity of calls by the grading of fear, pain and distress is quite different from any of the infinities considered here. It may be that in some species, particularly birds, different calls can be combined, sometimes one inside another. Observations to this effect have sometimes been interpreted as countering the claim that recursion in the system is human-specific. Similar interpretations have been made of variations in the calls by chimpanzees, vervet monkeys and others. It may be that some species, particularly chimpanzees, are better able to remember a large repertoire of calls. And other species are better able to understand them separately and to combine them. A combination of two calls goes beyond a mapping. But it is limited to the square of the calls. The output is finite. The interpretation that either of these evolutions are steps on the evolutionary path to human speech and language seem to me to miss the point that that the end-state of linguistic competence involves the simultaneous variation of both form and meaning. It is this, I propose, which allows the human-specific property of free compositionality and a similarly human-specific pathway to linguistic competence in normally developed human adults, taken for granted in all human cultures. But this leaves the core question, how did this human specificity emerge? By the proposal here, it can only have emerged by minimal steps in a population with a well developed communication system mapping calls to meanings, but making a fundamental cognitive break by defining the relation here. In the newly diverged human ancestors, the number of calls may have increased in response to the extreme dangers and opportunities of a ground-based environment. If that happened, the capacity to remember and understand different calls may have been pushed to the limit, perhaps beyond the limit. At some point, at least one call was reconfigured in such a way that it could constitute the first step to modern speech and language. From the fact that there are corresponding phenomena in all languages, it is reasonable to suppose that all of the steps proposed here were made separately, as an evolutionary sequence, in a population from which all humans alive today descend. At each point when a necessarily very obvious and visible step was taken, this was valued throughout and across a population. It had to be, or it wouldn’t have diffused and fixated. But while the capacity for speech and language clearly distinguishes humans from any other animal, and mostly develops naturally without any active intervention, this is obviously not the case for all, with 1 child in 10 having minor problems with speech and language, 1 in 1,000 having major problems, and perhaps 1 in 100,000 being unintelligible in adulthood other than to close family and friends, if at all.

- Interfaces. By conceptual necessity there are at least two interfaces, one involving physical expression (either by speech or by sign), the other involving the analysis of meaning. Information has to be sent to these interfaces in suitable, necessarily-different forms. The distinctively human lexicon is defined by the way this relation is defined in the brain at the point of acquisition. Both interfaces are limited by general factors of human cognition and the physical universe, including the acoustic phenomenon of sounds dying away as the energy is absorbed by the atmosphere or the fact that once a sign is replaced by another, the first is gone forever. The proposal here makes no particular claim about how the cognitive evolution of speech and language connected up with cognition itself or with any of the physical changes. We just have to note that these changes were in one species, and cognition, language, the physical apparatus, and lifetime experience, must have complemented one another.

- Seven steps. The Faculty of Language, FL, as it currently exists, could not have evolved its precise character other than by discrete, necessarily ordered steps, each one unconscious, most of them originally proposed by Chomsky. This is understanding FL in a very broad way, distinguishing all the various uses to which language is put, including the case of irony where the intended meaning is quite different from the literal meaning. The steps proposed here provide a framework for the much more narrowly defined structures of what is known as Universal Grammar, UG, and a foundation for language acquisition. The seven steps postulated here were taken by a species which had forsaken the safety of the trees for a much more dangerous life on the ground, after making at least six significant precursor adaptations. This was a population which either lived on its wits or died, as many sub-populations did. The population remained very small, but ranged across Africa while what is now the Sahara desert was forested and well-watered. Within this population, individuals or groups of individuals must have started restructuring some of their expressions in detectably advantageous ways, but by no more than one term at a time, so that, over the course of thousands of generations, the innovation could diffuse across the population, and (separately) become part of the genome. Following Progovac (2015), there must have been a series of protolanguages, each likely to have left fossils. As the linguistic genome evolved, the effects of the steps interacted with one another, giving the complex variations which Roberts (2022) characterises as ‘building blocks’. An abstract Universal Grammar UG is derived from the evolution of the human species. But there is cross-linguistic variation in how it is used – for example in which parts of the sentence structure are projected where – with global effects on word order and other aspects of what is commonly characterised as ‘grammar’. While a language may not express one or more parts of UG, all languages, spoken and signed, are built from it. The universality here is only very partially expressed at birth, just as the abilities of particular bird species to hover, stoop, dive and soar, are expressed only as the fledgling develops. But all of these steps are entirely unconscious,. In a way more complex than the particularities of bird flight, the full integration of UG elements into FL continues until at least ten or so for most children. The evidence for the evolutionary sequence proposed here is from the acquisition of language, language disorders, the differences between languages, creoles, signed languages, the commonalities of unrelated languages, the detailed examination of any one language – for our purposes here, English, and the special, possibly world-unique, case of Nicaraguan Sign Language. The acquisition evidence is from the similarities between the examples given and the fact that they occur in a matching sequence across all members of a sample of children. By the reasoning here, modern speech and language acquisition exactly replicates its evolution, in a way unlike other areas of comparative biology. In the absence of any evidence that acquisition proceeds differently from evolution, acquisition and the Nicaraguan evidence may provide the closest approach to direct evidence of the possible, probable, or even necessary course of speech and language evolution.

- Timescales, tools and talk. The evolution of speech and language began earlier and proceeded more gradually than by Berwick and Chomsky’s proposal, but still very briefly for a change of such complexity and significance. From paleo-anthropology, it is possible to define an earliest plausible beginning of the evolution of speech and language – no earlier, I submit, than the first manufactured tools intended to last (by the results of Sonia Harmond and others (2015) about 3.3 million years ago), and no later than about 135,000 by the results of Shigeru Miyagawa and his colleagues (2025). I propose that human style stone tool making must have preceded the evolution of language because knapping flint requires an awareness of geometry, quite different from and cognitively far beyond the various skills exhibited by chimpanzees and other non-humans. This was plainly an enormously difficult cognitive step, taking at least three million years from the point at which human ancestors diverged from chimpanzees. The likely time scale of human language evolution is by hundreds of thousands of years or thousands or tens of thousands of generations, in contrast to normal, modern-child development over months and single years. This says says nothing about the exact time scale here for each step or about how quickly the steps in language evolution fixated across the ancestral population. If it took modern human ancestors at least 3 million years to learn the essential geometry of knapping, it would seem reasonable to assume that the incomparably more subtle process of encoding UG on a spine must have been similarly challenging.

- Encodability. By each step, by evolution and by modern acquisition, the human organism’s sensitivity grows to a particular, mathematically defined, degrees. The sequencing of the steps is by five necessary factors, by the internal logic of the steps themselves, the dictates of discourse and conversation, general human cognition, the criterion of heritability, and the mathematical representation of biology. The factors are justified by the clear evidence of biology in disorders of all sorts, including stammering and problems with the articulation of words and putting them together in grammatical structures. All of these things run in families in ways not accountable by immediate contact. For instance, a child can sound like an uncle or aunt at the same age or a close relative brought up in another language. Such sorts of genetic evidence are found in around 30 percent of all disorders. But biology does not, cannot, operate with any properties defined solely on linguistics, such as consonants, vowels, or sentences. The binary branchedness assumed here (on the basis of 40 years of research on this point) has to be definable in a way that can be can be encoded mathematically, as set out by Matilde Marcolli (2022). This biological ‘encodability’ allows linguistic structures to be entered into a computation in a way applying to any natural language, whether spoken or signed, now fixated as a defining genomic character of our species, anatomically-modern Homo sapiens. As shown by Sandiway Fong (2023), this genomic factor is limited by neuro-physiology; synapses take around a millisecond to transmit from one nerve cell to another, and much longer to recover. Given the complexity of what has to be transmitted, this is slow.

- The reverse of discourse. Language, as characterised by UG, is defined on structures, which are put together so as to lay the basis for a potentially infinite output. UG contrasts with discourse, anchored in the here and now of conversation, expressing the use of language to relate utterances to the context in which they are uttered, to express emotions, to interest, to entertain, to elicit information, or to be ironic by reversing the overt sense of an utterance. Even at the very beginning of the evolution, it is possible to imagine discourse functions as soon as there are distinct meanings in particular expressions. Modern language is both used for discourse and subject to UG. UG is structured in such a way that meanings can be both shared and defined. But the structure of UG is quite different from the recognition of other speakers and other points of view in discourse. Discourse and UG are separate domains. Neither makes sense without the other. By the proposal here, both are separately articulated in relation to grammar. There is interplay between the two systems in both directions, with syntactic expressions becoming curses and attitudinal expressions getting turned into words. Plainly, the first words are not exclusively defined by either system. As a child’s language develops, these articulations of discourse and UG become increasingly well-defined.

- Reducing the infinity. in a rather surprising way, each of the steps postulated here in the evolution of UG with its infinite generative capacity, involves the step-wise reduction of the elements involved at any one point in the derivation. The first step, characterised here as Lexicon, first decomposes, then recomposes, two sorts of unlike atom, one expressive, the other semantic, and defines this relation for what it is. Lexicon gives a starting point for this aspect of evolution and ontogeny. It allowed what is known as Universal Grammar, UG, to start evolving. By the proposal of Martina Wiltschko (2014), UG is defined on a ‘spine’ or a headed decision-tree, with binary branches’, rather than on a set of grammatical functionalities such as passives, as in “She was hit by a falling tree”. Language-specific variations, such as the form of the passive, are defined on derivations from the spine, interactions between these derivations, and the ways that these things are implemented in speech. These variations are part of the learnability space – what has to be learnt in different ways according to the language being learnt, as finitely varying points of variation known as ‘parameters’. By the proposal of Chomsky (2000) and much subsequent work by Chomsky and others, the derivation is factored into ‘phases’, each defined on a minimal set of elements, such that at any given phase, much of the content of previous phases is no longer accessible to the computation. The ‘workspace’, as this is referred by Chomsky and others (2023), is minimised. The force of a structure is treated separately from its propositional content. By the proposal here, the spine is itself a mathematical structure. This reduction of the workspace is arguably what makes the grammar finitely learnable, as it patently is. By conceptual necessity, this has to be the last of the steps proposed here. Both the notion of a phase-based grammer and the term ‘spine are now widely accepted. By the proposal here, the spine itself is phased.

- The recognition of fitness. Each step must have been noticed and recognised by potential mates for what it was, a greater fitness, leading to a consistent bias in mate selection, ensuring that it eventually became inheritable. In terms of statistical dynamics, the greater fitness may have been marginal. But a slight bias applying consistently over one or more thousands of generations can effect a change in the genome.

- A single sequence of steps conferring a single faculty. Resurrecting the approach of Chomsky and Halle (1968), the seven steps here give speech as well as language. Crucially this evolution provided a grammatical apparatus which was, and is freely used in assembling words together and in the building of speech sounds, in ways that the child has to learn. While the phonology of this falls outside the main scope of the evidence here, the apparatus may be over-used in the process of speech acquisition so that children often use devices in the building of words which should be used only in the assembling of words into sentences. The phonological apparatus is such that speech-disordered children from different generations or parts of a family often have recognisably similar issues. By virtue of the sequence, the grammar becomes available in parts. In terms of syntax, the topic of most of the evidence here, a normally developing child of two and three quarters can say “A clock tells you what time it is” displaying the first evidence of Phase long before the full functionality of the grammar has emerged, as it mostly has around seven years later. All that can be said is that the encoding is separate from the communicative advantages. For instance the convenience of using pronouns has no obvious relation to the unobvious adjacency of levels on the spine. If the proposal here is on the right lines, one or more of the last evolutionary steps may have occurred after the divergence between modern human ancestors and Neanderthals and before more or less anatomically modern humans appeared in what is now Western Morocco around 300,000 years ago. Inheritors of the epigenetic changes by the last step in particular would have learnt to talk faster, more accurately, more reliably, and crucially more completely. We often refer to someone having ‘the gift of the gob’ as a characteristic talent of chat show hosts and comics, uncommonly able to spot and develop a double entendre and more. The first inheritors of Phase would have sounded even more talented, standing out even more sharply in competition for mates. By the resxults of Miyagawa and his colleagues (2025) Phase must have fixated across the ancestral stem of anatomically modern Homo sapiens by around 135,000 years ago. It seems likely that Phase critically reduces the learnability space, making speech and language finitely learnable for the overwhelming majority in what Eric Lenneberg in 1967 called the ‘critical period’ for language acquisition, normally ending around the age of ten. This linguistic advance would have marked homo sapiens apart from any pre-existing human species, including Neanderthals already established in Europe and central Asia. It thus may be that it is Phase which makes language finitely learnabable as it demonstrably is for the overwhelming majority, that language was not finitely learnable without it, that without Phase, there was a wide range of linguistic competence across the ancestral population, with only a minority having access to anything resembling the complexity of modern grammar. How small this minority may have been, how grievous the effects of relative incompetence were, and in what proportions, where the grammatical defects may have appeared, are all impossible to guess. As Phase and conjecturally finite learnability spread across the population, communication between conspecifics sharing this faculty became critically more reliable. In dealing with everyday emergencies, at critical points in hunting dangerous prey, in disseminating advances in technique and technology, reliable comnunication became a decisive asset. Finite learnability and the consequential reliability of communication between conspecifics would seem to have given a great advantage at the point of population survival to those having a phase-based grammar in relation to any group not having it. The difference may have been critical, with Neanderthal mastery of speech and language mastery uneven, with no expectation of common understanding. Neanderthals may have been stuck at the point when only a fortunate minority had a full mastery of their linguistic inheritance, whatever that may have been, and the rest of the population had only varying degrees of competence and little or no metalinguistic ability. In competition for scarce resources, the reliability of communication between conspecifics may have enabled modern Homo Sapiens to prevail decisively over the established Neanderthal population in a few thousand years, soon developing the first indications of modern culture in jewelry, wall-paintings, sculpture, musical instruments, not to mention stone tools. While there is a learning process which is normally completed across the whole population, this is not so for all. As Carol Chomsky showed in (1969), many ten year olds are still misunderstanding sentences like “I’m asking you what to feed the dog” as “I’m telling you what to feed the dog”. She suspects that some individuals may not proceed to a full understanding of this point. On a phase-theoretic analysis of the error here, the subject of the ‘feed the dog’ phrase is incorrectly not projected up to the topmost phase, represented in this case by the first person pronoun, I.