Framework or hierarchical structure

Once known as 'Transformational Generative Grammar', now known as 'Biolinguistics'

And two hidden dimensions

By the framework here, language is organised in three dimensions, one obvious, two not obvious at all.

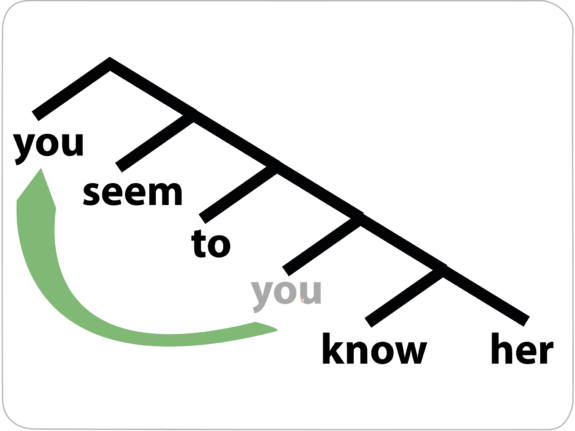

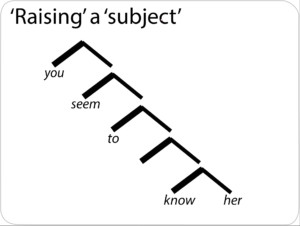

The obvious dimension is in the fact that sentences have length and and left to right ordering. In the spoken word know, the N sound precedes the OH sound, and in the expression, “You know”, you comes before know. The sentence “You seem to know her” has five words. But in the way it is understood, you relates to know rather than seem, as shown by the fact that “It seems that you know her” means almost or exactly the same thing. You is displaced to the left edge of the sentence. Or ‘raised’ by a version of the framework here, diagrammed above.

The obvious linearity is a necessary consequence of the fact that no matter whether the structure is heard in speech or seen in sign language, human articulation, perception, and memory work in a linear way. The visual medium of sign allows the two hands and head and eyes to do different things at once in ways impossible in spoken language. But even in signing there is still an inescapable sequence.

Largely by the work of Noam Chomsky from 1955 to 2023, two hidden dimensions have been discovered. There is DOMINANCE in the vertical dimension and DERIVATION in time. By the framework here, the length of structures is an artifact of the derivational depth, rather than the other way round.

The hidden dimensions are captured by the branchedness in the diagram above, now commonly known as a ‘spine’, built from the bottom up. The branching can continue, as by the diagram above, indefinitely. One hidden dimension is from bottom to top. A second hidden dimension relates the elements by each branching according to their roles. This simple device makes language infinitely creative, using only one simple procedure or operation. All human languages have this infinite creative potential.

By the proposal here, human language started to evolve when the first gestures with meaning and some phsical expression were mentally defined on the basis of this relation of complete unlikeness between the members of this set, the set of the members of an expression. This was the beginning of the modern lexicon. This to have been the very first step in the evolution of speech and language. (These gestures may have been vocal or with the hands and body. I think that the weight of the evidence favours a vocal origin.)

It might seem logically posssible for speech and language to have evolved from single words which were then combined by a simple function putting one word after another. The possibilities are limited by the number of words or signs. But as Marinus Huybrechts (2019) shows, a function with an infinite output can’t grow out of a system with a finite one. If this line of reasoning is correct, as I believe it is, what the small child is doing by his or her first word is rather more sophisticated than it might appear to be. Even the first word is built from the same structure which allows linguistic structures to grow ad infinitum. So human speech and language development has to START with a potentially infinite output. This leaves a tree structure as the only possible starting point. There is no way of characterising the pathway from single words to the five words in “You seem to know her” other than by postulating a potential branchedness in the simplest structures.

Immediately below I show only the first and second branches.

The diagram here represents a process known as ‘derivation’, representing structures, not sequences or chains of elements. By this modeling, a structure can grow from one branching to another. Consider “Did you do the washing up?” and “You did not do the washing up.” Did and do are formed from the same do root used in different ways in English. But in both cases do is pronounced in between did and washing up. And you in the first case and not in the other are prononnced in between did and do in what is clearly a verbal element. In a similar way, the equivalence between “Can’t you just do it?” and “Can you not just do it” can be characterised in terms of the position in the chain of branchedness of the negative form according to whether it is fully pronounced as not, or pronounced only by the consonants and without the vowel, as ‘NT. one branching further up the chain. In the simplest negatives and questions, there is displacement as in “You seem to know her”. Now these complex orderings can be described as different positions on strings, as they are by some theories of grammar. But these theorisations seem to me more complex than by tree structures of the sort disagrammed here.

Since 1995 Chomsky has charactersed sort of structure in terms of the ‘merging’ of one element with another. It applies ‘recursively’ – over and over again. These two hidden dimensions are not a figure of speech, but a representation of the underlying algebra of the cognitive process here. These dimensions are hidden, We are as unaware of them as we are of gravity. Like gravity, they can be detected only by induction. What we are aware of, words and signs, are just the necesssary ‘externalisation’ or ‘linearisation’.

The hidden dimensions

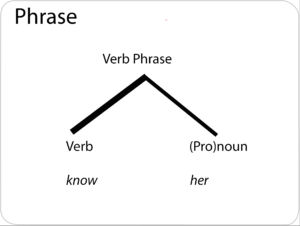

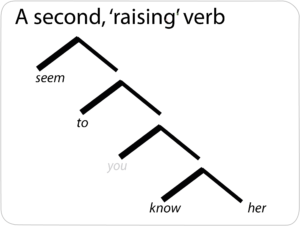

In “You seem to know her”, the deepest relation is between know and her. The two words differ on the point that her picks out some individual female known to the speaker and listener, and the verb, know, plainly does not refer. The ‘know her’ clause, traditionally described as ‘subordinate’, is generated as the first derivational step.

Know is said to ‘project’ as the defining element of the branch, and shown by the heavier line in the diagram of a ‘Verb Phrase’ here. Know is thus the ‘head’ of the resulting expression. The history of how the expression was formed is preserved in the verb phrase label.

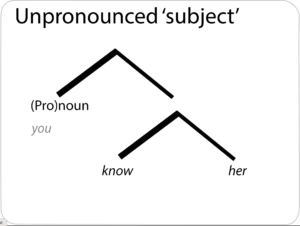

The notion of you as the knower is reflected in the next derivational step, by which the bare bones of a sentence and a meaningful proposition, either true or untrue, is created. But you is not pronounced at this position, as shown in the diagram below by greying.

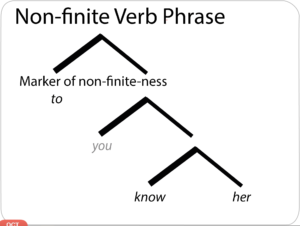

The non-finiteness of the clause, the fact that the verb is not marked for tense is shown by the word to.

The main link between the clauses is by the special property residing in the verb, seem, calling into question the certainty of the knowing.

By the final step in the derivation, a slot is created for a nominal subject of seem, filled by you copied from its original position, and ‘raised’ to a higher position by a further grammatical event. For the purposes of pronunciation, you is ignored in the position where it originated, although it remains there for the sake of understanding.

There are thus two hidden dimensions here, one in the fact that the derivation is by steps, and the other in the fact that resulting structure has depth.

What does this quite intricate structure achieve? Would it not be simpler to say just that the ordering in “you seem to know her” is associated with a particular meaning? The problem with a strictly linear characterisation is in the definition of the ordering. It aseems to me that there is no plausible way in which the necessarily very complex grammar could plausibly have evolved.

This situation has led to the postulation of what is commonly referred to as ‘Universal Grammar‘ or UG. The notion of UG does not propose (absurdly) that there is just one language, but just that there are deep and very significant commonalities across all languages, and that the commonalities are at least as important as the obvious differences. As Roger Bacon put it in the 13th century, “In its substance, grammar is one and the same in all languages, even if it accidentally varies.” Much the same point was made by the famous Roman scholar, Marcus Terentius Varro, just before the birth of Christ. But these insights were overlooked by scholars until this thinking was developed much more fully by Noam Chomsky in the 1960s.

Maximally binary branchedness

The structures here are shown in the form of rooted, planar, binary-branched trees. Such trees are mostly represented with the root at the top and the leaves or ‘terminal nodes’ at the bottom. The terminology and the graphical representation are thus not in line with one another. The representation is upside down. Here I am just following linguistic convention.

One aspect of such trees which seems to me insufficiently remarked upon is that binarity is forced by neurophysiology. A nerve either fires or it doesn’t,

A counter claim

The frame work here is commonly criticised in relation to a much cited article by Hauser, Chomsky, and Fitch (2002) where it is proposed that the distinctively human property in language is the ‘recursion’ by which one structure, such as ‘know her’ is embedded inside another structure, in “You seem to know her”, with the raising verb, seem.

Daniel Everett (2009, 2013, 2018) claims to have found a language which lacks this capacity. He claims that he was not able to hear any instances of recursion in the language of the 500 members of the Amazonian tribe which he studied, recursion can’t be universal. The language, known as Pirahã, is spoken by one isolated tribe of hunter gatherers in the Amazon. Everett appears to have been the first outsider to make contact with them and learn their language. He claims that it is simply impossible in Pirahã to say anything like “You seem to know her.” But, as David Pesetsky, Andrew Nevins, and Cilene Rodrigues (2009) show, there are good reasons for doubting Everett’s claim. They show that Everett misrepresents his own data. The argument rumbles on. But Everett is in a very small minority in arguing that the framework here can be discredited in its own terms.

The direction of thought

It is sometimes thought that the main focus in the analysis of child speech should be on what children most often get wrong. But that does not answer the questions: Why do children get wrong what they do, not just individually, but generally? And how do they end up talking ‘correctly’, understanding one another, and agreeing about meanings? To find an answer, I propose to consider what learners HAVE to attend to and how human speech and languaage have evolved the structures they plainly have. The two considerations of what the language learner must be attending to and what must have happened in the evolution of speech and language are what justify and motivate the research program and the proposal here.