A mathematical basis

Sets, building and branching

At most two ways

By a widely adopted model of how human language works, the grammar is entirely built from sets with just two elements, mathematically {a, b}, for any set of entitities. This model has been developed in a vast tradition of technical research over the past 30 years, building on research over the preceding 30 years. It has a strong theoretical and empirical basis. I adopt it in the framework here, and develop it in the proposal here.

For the sake of illustration, a set could be the set of pots and pans – in one kitchen or the entire universe. The relevant linguistic sets have come to be commonly described in terms of branching or branchedness.

On the basis of a proposal by Noam Chomsky (1995) all combinations of words in all languages, even by the longest and most complex sentences, involve the same simple mechanism of ‘merging’ two forms together, then merging this with another word or set of words, and then repeating the same operation over and over until some given structure is complete. From start to end, each step of merging involves a set of two elements, with each set possibly built from other sets. To emphasise that this was a new direction in resarch rather than a new theory, Chomsky called this “The Minimalist Program”.

In typical child language this is exampled by “Horsey looking”, as a partial sentence structure with a subject followed by a verb, or “Looking horsey”, as a partial ‘verb phrase’ with a verb followed by an object. In both cases two words are merged with a particular relation between them.

Now it might be said that this is just the same as stringing words together, one after the other. But there is an important difference between a string of words and a structure of mergings. By merging, but not by stringing together, the structure is made up of elements, each defined in a particular way. And these elements can be manipulated in various ways. In “Horsey looking” and “Looking horsey” it is likely that two quite different ideas are being expressed, one with horsey at the subject and the other with horsey as the object. But in “Where horsey?” it seems that a aquestion is being asked. And in “Like” and “No like” or in “Like milk” and “No like milk” a given structure, “Like” or “Like Milk” is preceded by no, reversing the truth value – and probably the whole force of the expression. In this way, for the simplest sort of negation (in this case rejection), the structure is being manipulated. Now it might be said that what the child is doing here is just saying no as the first item in a string. But “No like milk” isn’t English. It is child English. In order to describe and explain how the child’s English form gradually becomes “I don’t like milk” with the not losing its vowel and getting stuck onto the end of do which then changes its vowel, and doing this in the middle of the sentence, between the subject I and the verb, it is useful to invoke the notion of structure.

As the power of the grammar develops, “The chimpanzee doesn’t like being looked at” becomes fully understandable. The same sort of idea might be said as “The chimpanzee doesn’t like you looking at her”, but that personalises matters unnecessarily. The point is just that for chimpanzees, as for some other apes, prolonged eye contact is threatening. So the idea is better expressed by changing what is known as the ‘voice’ of the verb from looking at to the ‘passive’ voice in being looked at with the word being before the verb and sticking an -ed onto the end of it.

This particular manipulation is unusually complex in English, but common in everyday use. And it takes children a number of years to learn how to manipulate all the relevant parts of the structure. But it is only possible by knowing exactly which words need to be manipulated and how. The simplest way of defining the possibilities here is by having the words in a structure of branches as opposed to a string. It is possible in principle to characterise these two manipulations as operations on words in strings, but as Noam Chomsky noted in 1957, only by making the grammar enormously more complex.

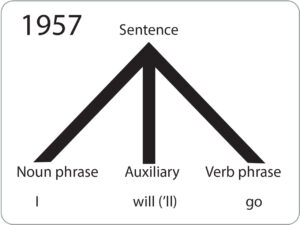

Now by Chomsky’s 1957 analysis, branching could go three ways, as shown in the diagram below of “I’ll go” with the sentence comprising a subject noun phrase I, an auxiliary will, and a verb phrase consisting of the intransitive verb go.

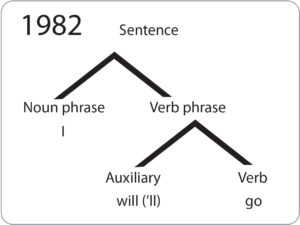

But by 1982 it was found that there was a more restrictive and thus better analysis by restricting the branching to two ways at most. This is more restrictive in as much as it bears on the fact that even though there is wide variation in the ordering of subject, verbs and elements with the function of auxiliaries, some orderings are much commoner than others. This was one of the first steps towards what is now known as ‘Minimalism’ in linguistics and ‘Biolinguistics’.

Subject to this new constraint of maximally binary branching, as this is known, the auxiliary is shares a head with the verb, go. And this structure is then related to the subject, I. The fact that the contracted form, ‘ll, gets stuck onto the subject, as in I’ll, does not bear on its position in the structure.

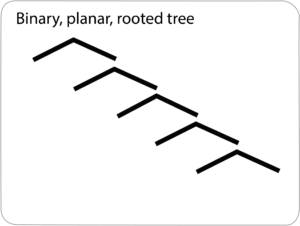

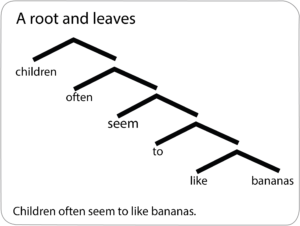

Since each branch represents two elements. the branching is said to be ‘binary’. By the simplest, logically possible case, the branching is in only one plane. So it is said to be ‘planar’. Since the branching starts at a given point, it is said be ‘rooted’. And the structure is said to be a ‘tree’.

An atom is mostly, but not always, what is commonly regarded as a ‘word’. (The combinations are in one sense more than words and in another sense less than words.) In the expression “Like bananas”, like is ‘merged’ with bananas’, and to with like bananas, to form an expression where there is no indication of who is doing the liking, or when. In this way, the same procedure can apply successively or recusively to its own output. By applying to its own output, Merge can generate an infinity of structures. Conventionally, the root is shown at the top, and the leaves, in this case the words, as these are pronounced at the bottom, as sketched below – biology notwithtanding, by the standard convention in mathematics and linguistics.

Chomsky and others (2023) argue that Merge is the one and only operation of the syntax – what is commonly known as the ‘grammar’. Robert Berwick snd Noam Chomsky (2016) argue strenuously for the notion of Merge by a single, recent, evolutionary mutation. In subsequent discussion, they argue just as strenuously that it is indivisible/

The core motivation of this approach is thus to explain WHY the structure of a language is the way it is and HOW it is reliably learnt despite the infinite, random variations in children’s language experiences.

The proposal here adopts this derivational approach, and takes the singularity of Merge as its inspiration, but extends back in evolutionary time before Merge worked the way it does in modern language, and on to its subsequent development.

The system that exists in modern human language is exclusively binary. And this could not have plausibly changed in the course of evolution. The system must have started off that way. There is a binary relation in nervous systems. A neurone either fires, or it doesn’t. There is nothing in between. So the step-wise structure of speech and language necessarily starts with the combination of two atoms or ‘leaves’.

Isn’t this a case of angels dancing on pins? Not quite. Suppose your child is at the single word stage for longer than most children and perhaps only saying one single word, what is the point in even considering the next stage when your child appears to be nowhere near it? Actually, there is a simple, very good reason. As shown in Single words, even the first word itself has a subtle but important structure. It may seem to be very simple, like what sounds like CA for cat, without the final T, in other words, a consonant and a vowel in that order each with their own internal structure representing an entity in the real world, seemingly not a call for help or an expression of fear, but at the very least a simple observation – effectively “I can see a cat”.

Branchedness in speech as well as language

Also, by the Proposal here, developing an idea from Nunes (2002), phonology and syntax have evolved and are learnt by children by the same algebra. By Nunes (20o2), the notion of maximally binary branching allows a corresponding analysis of speech sounds being derived from pairings, rather than formed in any more complete units, such as ‘phonemes’. By this approach, branching, subject to a generally accepted restriction, applies across the board – to words or signs, to their assembly together, and to their constituent acoustic or gestural features.

Consider the cases of the first sounds and only consonants in pea and bee, key and ghee, tea and Dee. In each pair, the first sound is said to be ‘voiceless’ or ‘unvoiced’ and the second is said to be ‘voiced’. In all cases, there is a complete closure of the vocal tract in the mouth, in P and B by the lips, in K and G by the back of the tongue and the soft palate or velum, and in T and D by the tip of the tongue and the alveolus or the hard palate just behind the front teeth. So P and B are said to be labial stops, K and G back of the tongue or dorsal or velar stops, T and D tip of the tongue or ‘coronal’ or ‘alveolar’ stops, in each case the first voiceless, the second voiced.

But there is a puzzle from children’s speech. The commonest immaturity, often called a ‘process‘ is the systematic replacement of K by T. So many children say key as TEA, cow as TOW, and car as TAR. This is commonly known as ‘fronting’ because the articulation of T is closer to the front of the mouth than the articulation of K. Now it might be hypothesised that it is just easier to articulate the tongue tip than the back of the tongue. But in this case, why is doggy commonly said as GOGI, with the replacement or assimilation going the opposite way, favouring the back of the tongue rather than the tip. This is especially surprising given that the G is in a perceptually less salient position in the unstressed syllable. And why is the common replacement of K by T, rather than by P?

The relevant speech sounds or phonemes can be schematised as follows:

P – Voiceless stop articulated with the lips

B – Voiced stop articulated with the lips

K – Voiceless stop articulated with the back of the tongue

G – Voiced stop articulated with the back of the tongue

T – Voiceless stop articulated with the tip of the tongue

D – Voiced stop articulated with the tip of the tongue

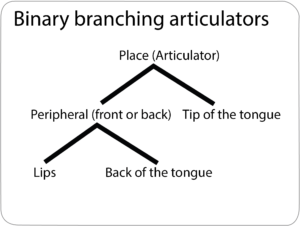

Setting aside the voicing which I list here only to encompass the case of doggy in relation to key, car and cow, there is what is commonly considered to be a three way branching between three articulators or places of articulation, the lips, the tongue tip and the back of the tongue. But if branching is exclusively two ways or binary in speech and language, there can be no such branching.

With stops as a universal sort of consonant, this set of three articulators in stops is typical across the world’s languages. By an extended notion of markedness, a contrast betwee three articulators would seem to be unmarked. While there are many different theories of how the articulators are organised, Nunes (2002) argues in detail for the following organisation (adopting the model of Carole Paradis and Jean Francois Prunet (1991):

If the articulation is derived in the following sequence, and if T represents a minimally specified articulation, there is a natural explanation of fronting by ordering the articulations as follows:

- Lips

- Back of the tongue

- Tongue tip

The characteristic error by fronting is to omit the middle step which is then implemented by default by the final step. It is not that the child does not know about the back of the tongue as a feature. It just doesn’t get articulated.

Nunes (2002) analyses an exceptionally severe speech disorder in a child of three and a half who was almost completely incomprehensible to her own mother. She had some assimilations to the lips, some to the back of the tongue, and some to the tongue tip. Her uncommonly complex system followed the sequence of Lips, Back of the tongue, Tongue tip. And she followed this sequence twice, first with special conditions, and then generally.

In other words, the notion of maximally branching in speech has a useful application where the development of speech goes badly wrong.

This approach is extended further by the Proposal here.

A brief take away

The notion of maximally binary branchedness has only been around for the last 40 years. But applied to both speech and language, it is enormously relevant in the most practical of ways to speech and language therapy.