Order, disorder, evolution

The force of evidence from modern language

Theodosius Dobzhansky (1937), Paul Nurse (2020), and many others, propose that evolution is crucial to any understanding of how biology works. Noam Chomsky (2022) proposes that this includes language.

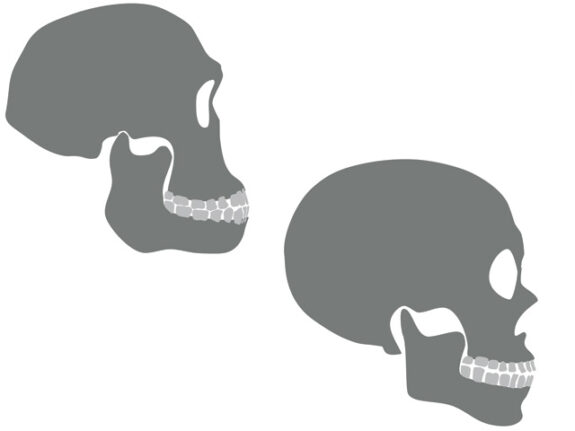

By the proposal here, in a way unusual in biology, the acquisition of speech and language almost exactly recapitulates their recent evolution. The one (big) difference is that at any given evolutionary point, what children heard and inherited was only what had evolved up to that point. The process of learning has almost certainly become much faster and more efficient, perhaps a million times or so, over the period of evolution.

In this evolution, there must, I propose, have been at least seven steps, the last being the least thoroughly fixated and thus the most vulnerable to developmental mishap. By the latest evidence, from Shigeru Miyagawa and others (2025), this point of completion is likely to have been around 135,000 years ago. There are two sorts of evidence for this proposal – modern language and the natural process of speech and language acquisition, both intensely studied. It should be said that this idea is not endorsed by Chomsky who proposes that human speech and language evolved by a single evolutionary step, and thus that there has never been any such thing as a ‘protolanguage’.

A merit of the seven step proposal here is that it reduces any need for postulating specific malformations, as proposed by Lawrence Shriberg et al (2005) and innumerable others in the same tradition. Shriberg suggests that it is necessary to postulate particular ‘phenotypes’ of disorder or malformations. The proposal here at least diminishes, if it doesn’t eliminate, the case for any specific malformations. An evolutionary model thus simplifies the theory of disorder. as required in science generally, by an idea generally known as ‘Occam’s razor’ (William of Ockham lived in the 14th century).

Putting this a different way, with a child who is not learning to talk by the normal schedule, the primary diagnostic task is not to elucidate which psycholinguistic functions are faulty, but to describe the problem as precisely as possible so that it can be plotted in relation to a necessary evolutionary sequence. What are otherwise referred to as ‘functional disorders’ become the natural consequence of any recent evolution. There are such things as ‘motor speech disorders’ or ‘psycholinguistic disorders’ – due to problems of physical coordination or perception. But they are relatively uncommon.

But in learning to talk there is a lot to learn. And some of the learning is in relation to the physical aspects of speech.