Linguistic competence

Certainties about meaning

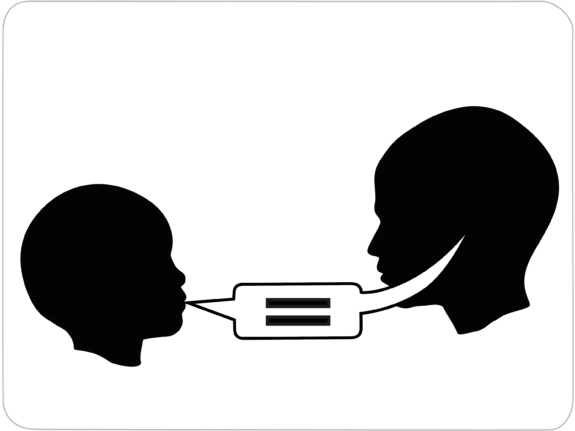

By an idea from Noam Chomsky in 1965, linguistic competence is what enables normally developed members of some human community to agree about what things mean or don’t mean or or how they should be said better or that they mean more than one thing, and if they do mean more than one thing, how many things they mean.

Judgements can be quite subtle. By the judgement of most native speakers of English “Who do you think that called the president a moron” is at least less good than “Who do you think called the president a moron”. In this case, the word that has to be left out. Some would say that with that the structure becomes ungrammatical.

In a more extreme way, “Something interesting” is everyday English, but “Interesting something” is almost uninterpretable, even though adjectives like interesting otherwise precede the word or phrase they qualify, as in “an interesting story” or “an interesting look in her eyes”.

Noting that in actual everyday speech many sentences are only half completed or are said with one of more words missing or the wrong way round, Chomsky contrasted linguistic competence with linguistic performance, what is actually said. In a way that seemed to contradict many scientific understandings then and now, Chomsky proposed that only linguistic competence was the proper object of scientific study.

My formulations here are just rough. From a scientific and philosophical point of view, it is possible to query every one of the terms here. What is it to be ‘normally developed’? What is a ‘human community’? What is it to mean? And so on. But there is an important sense in which this approximation says something about the world. About the notion of linguistic competence, Chomsky noted that “its most striking aspect… is what we may call the ‘creativity of language’, that is, the speaker’s ability to produce new sentences, sentences that are immediately UNDERSTOOD by other speakers although they bear no physical resemblance to sentences which are ‘familiar’.

The notion of linguistic competence is more than a theory. Without the expectation of common understanding, everyday human interaction would proceed only by continual guesswork about meanings and more general cognitions about agency, responsibility, truth, denial and so on. Modern society would come to a sudden stop.

Clearly there are different factors here, including children’s experience of language, their biological inheritance, and broader human cognition. The need for experience is obvious. The other factors need to be weighed against one another. Although there are wide variations in children’s experience of conversation with adults and child-directed and language, and these things clearly have a measurable effect on the speed of acquisition, the end point which used to be known as ‘linguistic competence’ seems to be unaffected unless the deprivation is truly extreme. In the 1920’s a team of researchers from Moscow visited a village on the far slopes of the Urals after ten days of traveling, the last three on foot. The village was picked as one likely to have experienced the worst effects of feudalism and czarism which had only been abolished ten years earlier. The researchers were clearly shocked at what they found. Although the notion of linguistic competence would not be developed for another forty years, it seems likely that the researchers found a significant proportion of the villagers who did not have a fully developed linguistic competence in the Russian dialect of the village. It is likely that there were similar demographics less clearly defined all over Russia, such as those who hauled or carted goods because they were cheaper than animals. As such degradation continues it is likely to have an effect on all the competences of all the children born into it.

In one tragic case, documented by Susan Curtis (1972), a child was kept locked up in a room for the first thirteen years of her life. The effect was to leave her incapable of developing normal linguistic competence despite the most strenuous efforts to compensate for those thirteen years of criminal deprivation. Other than by such criminality or the most barbarous effects of slavery and feudalism, linguistic competence is a universal commonality. The main variation is just in the timescale of acquisition.

But the fact that the notion of linguistic competence is just a first approximation has led to a long argument about whether the notion is even useful. It seems to me that the argument has been largely sterile. There are just highly polarised views. And to move forward beyond sterile argument, the notion of linguistic competence has been replaced by the term i-Language, meaning something similar, not quite the same, but not so easily turned into a whipping boy. To my way of thinking, this has been a step backwards.