Articulation and phonological problems and disorders

A continuum

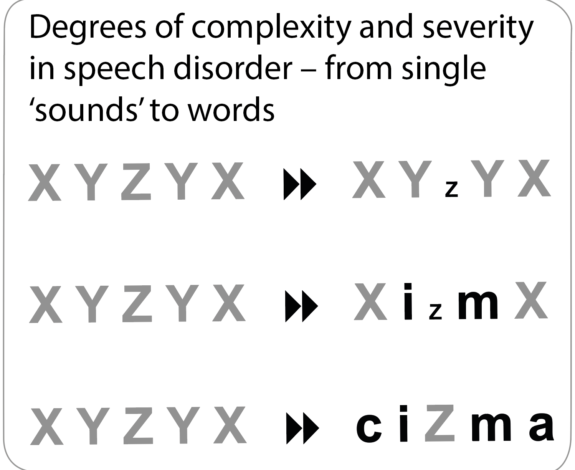

Articulation problems, including problems saying S and Z or SH or R, are commonly regarded as relatively minor issues, in contrast to more general issues affecting the pronunciation of many words, especially long words like the names of most drugs, newly identified species of plant and animal, and interesting sorts of dinosaur like diplodocus. Some instances of these problems are sometime categorised as ‘verbal dyspraxia’ or ‘Childhood Apraxia of Speech’ or CAS and sometimes as ‘phonological’ problems or disorders.

Does CAS represent the most serious sort of phonological disorder? Is a problem with a single sound or phoneme a phonetic issue in contrast to phonological issues, assembling any number of sounds into words? If so, where to draw the line or lines – if any such lines exist? The questions here are not simple. But the answers to them make a lot of difference to the classification , management, and treatment of speech disorders of all kinds. Which disorders can be successfully addressed at home or at school by carefully designed procedures? Which disorders require the involvement of highly trained specialists? And in all cases, which procedures and treatments are most effective? Big questions with big answers.

The 2007 ASHA Report

In 2007 an Ad Hoc Committee on Apraxia of Speech in Children, set up by the American Speech and Hearing Association ASHA, issued a report on its investigation of the possibility that CAS was overdiagnosed. In what seems to me a rather confusing way, the report concluded that CAS was indeed being over-diagnosed, but that the solution was to introduce a new category of ‘suspected CAS’ to be used in any cases of doubt. In a somewhat arbitrary way, the report set out which properties were definitional and which were not. But it did not define any borderline between CAS and phonetic or phonological issues. Nor did it ask about the borderline between phonetics and phonology, a can of worms if ever there was one, where there seem to be as many personal views as there are phoneticians and phonologists. From the characterisations of CAS, the issues seem to be more phonological than phonetic. The report listed many of the co-morbidities, including problems with syntax, literacy, and metalinguistics. On one, seemingly reasonable, reading of the report, there was no such thing as a phonetic or phonological issue. CAS just represented the serious sort of articulation issue. Perhaps significantly, in the 30 pages of references there was not one reference to phonetics or phonology. And although there was one clinical linguist, there were no phonologists or phoneticians on the committee.

Local and unrestricted processes

Consider the child who says, in a way that might not be understood, “I Taw you put your TeeD in De TinT”, meaning to say “I saw you put your keys in the sink”. Here there are what might be called two ‘processes‘, both common, one stopping the instances of S in saw, keys, and sink, and TH in the, the other fronting the instances of K in keys and sink, This would, most likely, be considered an articulation problem, involving three and a half substitutions, K to T, S to T, and Z and TH to D. If these are articulatory processes they seem to be strictly local.

Consider, by way of contrast, the four year old child, who was very hard to understand most of the time, who says, out of the blue, something like “A magiciam ib ma PiMe A wobuK.” Her mother did not understand her, And nor did I. I just made a note in phonetics. Her mother later remembered that they had just been to a friend’s birthday party where there had been a conjuror. And thinking about what we had heard, we worked out that she had been trying to say, “A magician is a kind of robot.” The lip closing action from the M in magician, the V sound in of, and the B sound in robot, had all got copied across the sentence, by a number of assimilations (making one sound match or assimilate to another), possibly encouraged by the lip opening action of the different O sounds in of and robot. Both the K and the N sounds in kind were substituted in the same way, being said as P and M respectively. And the T in robot had dissimilated to a K for no obvious reason. (In both the history of languages and in child speech, dissimilation normally has a clear ‘trigger’ – a match or near match which is unmade by the process. This happened in the progenitor of classical Latin, giving the R in solar, dissimilating the sound sound from the L, in contrast to naval, where the L is undisturbed, because there is no match with the V. Dissimilation is rare in the phonology of competent speech, but common in child speech, though commonly missed). Very unusually in this child’s speech, the Z sound in the functor, is, turned into a B. Functors are not commonly involved in such processes. If these are processes, such processes do not commonly span a whole sentence. Such unrestricted processes make speech almost unintelligible.

Obviously the child who stops S, Z, and TH, all tip of the tongue consonants, and fronts back of the tongue K has a less serious issue than the child who assimilates a lip action across the sentence, and dissimilates a final T, seemingly randomly. The second sort of speech is far harder to understand than the first. But are these qualitatively different sorts of disorder? It seems to me that there is no non-arbitrary way of distinguishing them beyond just categorising them on a scale of comprehensibility. At different points on the scale, different interventions may be appropriate, with Possible Words Therapy probably appropriate only for the second. That was how that particular child was treated. After twelve treatment sessions her speech was age-appropriate.

From a local articulation issue to one of complex derivation

For the child with stopping and fronting, a more phoneme-based approach, as by the Nuffield Dyspraxia Program, would seem appropriate. One child I saw initially for fronting and stopping, and successfully treated on that basis, I kept under review for a number of years. At one of these annual check ups, she still had a number of issues with various polysyllables. For instance, she said cardigan as KAHDINTAN, with three processes, fronting the G, devoicing the resulting D to T, and copying the N into the preceding syllable. Looking at that form in the context of other errors made by other children trying to say cardigan, the processes clearly happened in that order. But a proper analysis of the derivation here is currently beyond me. She then had six sessions of Possible Words Therapy, and all the issues with polysyllables that I had been able to find had been resolved.

A aingle pathway

The simplest account of such phenomena is that, as by the Proposal here, there is a single pathway to competent speech which can be disrupted to any degree at any point. I therefore do not believe that there is any ontological distinction between these apparent degrees of disorder. They are just that, points on a single, but complex, continuum, involving phonemes, syllables, phonotactics, word-stress, and syntactic categorisation. particularly between content words or lexical items and functors.