Language delay and language disorder

Sociology, evolution, and two opposite directions

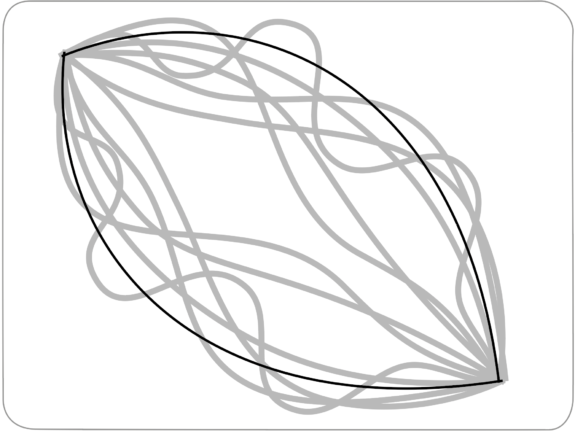

It is rather obvious that there are stages in children’s acquisition. And there is a pathway, about which I make a proposal here. There is a typical pathway. And there are non-typical pathways. What is not so obvious is exactly what the stages are and different pathways can seem to a single convergence. There are two sorts of theories of the stages, from sociology and from the theory of evolution. The definition on this point makes a lot of difference to speech and language therapy and the treatment of disorders and serious delays.

It is also obvious that there are quite wide variations in the schedules that children follow along the pathway. Some children follow a much faster schedule than others. But some children get stuck, or seem to take a wrong turning. These are the children who need help. Some children grow into adulthood without completing the pathway. They may be acutely aware themselves of the issue, sometimes saying: “I can’t say long words.” Before they reach teenage, when the natural process of speech and language acquisition normally comes to an end, these are the children who need help the most. Telling which children are most likely to end up as adults without completing the pathway, or by what margin they may not complete it, is not easy. But it is important, in my view, to ensure that the process of evaluating progress in speech and language therapy is sensitive to any indications one way or the other, that the child is getting back onto the normal pathway or seeming to have difficulties in this.

Before children start using actual words, most children babble, forming the same syllable and repeating it a number of times, seemingly without meaning. Some children babble a lot. Others babble only a little. Profoundly deaf children often babble a little before stopping, presumably because they can’t hear what they are doing. To my way of thinking, babbling is rehearsing one aspect of speech and language, the fact that it involves a physical expression, and ignoring the other aspect, that it also involves meaning.

Then, around or shortly before the age of one, children start using single words. Roger Brown, in his seminal work, A First Language, The Early Stages (1973), analyses the possible complexity of even single words. These “cannot, by definition, be sentences, but they can be expressive of greater complexity than the naming of single referents” (p.186).

By the next stage, perhaps three months later, but sometimes as much as a year later, children start putting words together. At this stage of language development, there are two sorts of words or expressions.

- There are words like bus, car, lorry, cat, birdie, ice cream, which in adult language it does not make a lot of sense to say on their own as ways of starting a conversation. Such words are sometimes known as ‘content words’, and by linguists often as ‘syntactic objects’ because they be entered into the syntax of statements, questions, and so on.

- And there words and expressions like hi, hello, bye or bye bye, oh, ah, night night, which commonly constitute items of discourse on their own, not part of any more complex structure, but sometimes said with any sort of syntactic structure.

Martin Braine (1962, 1963) made an initially influential proposal conflating all expressions consisting of either two syntactic objects like “See ball” and one syntactic object or one syntactic object and one discourse item, like “Hi, Mommy”. The first words in these strucgtures Braine called ‘pivots’. There were only nine or ten pivots in his sample, but a much larger number of what he called ‘open class words’ – what I am calling syntactic objects. But within ten years, a large number of studies, summarised by Brown, showed that even at this early stage, children’s speech clearly involved a more English-like abstraction than Braine had allowed. For instance, “See ball” clearly displays a verb and a noun in the order of an English ‘verb phrase’, as this sort of structure is known.

By a study that has proved more lasting than Braine’s, Brown proposes five stages of early language. By the fifth stage the grammar comprises:

- Semantic roles such as agent and patient, tense, and positive statement as by “I helped Daddy”;

- Questions as by “Is Daddy here?” and negation as by “Daddy’s not here”;

- Embedding “one simple sentence as a grammatical constituent or in a semantic role in another” as by “I see where Daddy’s going”;

- Joining sentences by and with what is known as ‘elipsis’ as by “Mummy and Daddy are coming” rather than “Mummy is coming and Daddy is coming.

But there are many different ways of modeling such a grammar, typical of children of between three and a half and four. By my proposal here, there are seven steps on the pathway to Brown’s fifth stage.

The distinctive character of the proposal here is that, as set out in Nunes (2024), is that the key data is in what children show evidence of getting right, and setting aside what they get only half right or get wrong. Other proposals dispute the need for any reference to what is purported to be the needless ‘abstraction’ of syntax. For the purposes of speech and language therapy, a lot hangs on the model that is adopted. The important thing is that there should be a model. Models can the be compared on the basis of evidence.

Many models assume a distinction between expressive or productive language and receptive language or comprehension. The distinction is motivated by the fact that children seem to reliably undestand structures far more complex than those they use in speech. By the model framework here, following a consensus of those frameworks descending from Chomsky (1965), there is no such distinction. For the purposes of both production and comprehension, structures are generated by the grammar. If there were two grammars the child would have twice as much to learn.

Some important aspects of grammar, like the elipsis interestingly noted by Brown, are very difficult to test, no matter whether the test is supposedly of their productionor or their comprehension. There is elipsis in the simplest answers to the simplest questions. In “Home” as a one word answer to the question “Where are you going?” the words “I am going” are standardly elided. But while the principle of elipsis seems to be universal across languages, the way it works in any particular language seems to be particular to that language. The mechanism has to be thusn partly universal, and partly language-specific. The necessary mechanism is the topic of current research.

Parents can usefully contribute to research and to their child’s therapy by noting in a diary any instances of elipsis in their child’e speech.

This is one of the areas where language seems to be pulled in two opposite directions, towards greater clarity on the one hand and towards gettting as much said as possible with the least effort on the other. Sociology suggests a focus through the lens of society. Evolution forces an account by the limits of what can be encoded in DNA. Sociology and evolution collide.