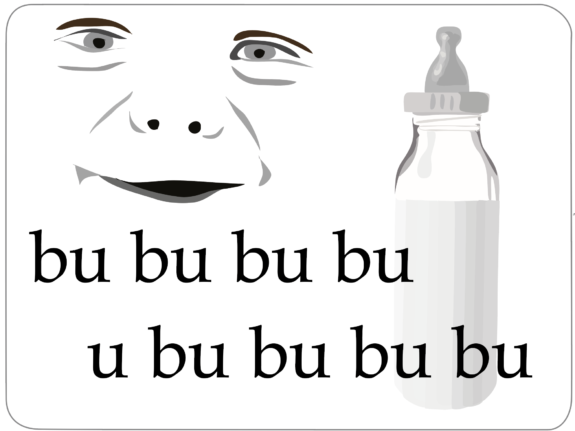

Babble

Experimentation with the sounds of language

From somewhere between 6 and 10 months (a long time in early development) almost all infants everywhere normally start to produce their own versions of the forms of the language they can see or hear being used. But the shape and pattern of this varies according to how they can hear and, if they can hear, the language being spoken. Hearing infants produce sequences of single consonants and single vowels BA BA, DA DA, MA MA, and so on. Such structures, known as babble, essentially prototypical syllables, are universal across spoken languages. But this is influenced by the language to which the child is exposed. Babble is like play with the sounds. The child is experimenting with what are known as the phonotactics, phonetics and phonology, of a given target language, but with no evidence of meaning.

Between 10 and 12 months according to Chia Chen Lee and her colleagues (2017) infants hearing tone languages like Chinese show subtle effects of the ambient language, starting to introduce characteristic Chinese elements into their babble, such as something like tones and final nasals, M and N, into their babble.

Languages like French contrast vowels spoken with and without the airstream passing through the nose. As children hearing languages like French approach the age of one their babble starts to include nasal vowels.

Profoundly deaf children of deaf parents coo and squeal like hearing children, but unsurprisingly show much less of the characteristic protosyllabic gestures of hearing children. But from around 6 months they start movements with their hands like those of sign language if this is being used in their family environment.

As shown by Weinberg (2015) infants exposed to more than one language display corresponding sets of influences on their babbling.

The relation between babble and speech has been deeply explored in many studies such as those by Marylyn Vihman and Peter Juschuk. But one comparison which does not seem to be commonly made is between babbling and the cooing of small chimpanzees and their mothers, plainly not a first step towards language.

Additionally, babbling is a way for infants to engage with caregivers, and these interactions often serve as a social bonding mechanism that is important for their emotional and cognitive growth.

Studies suggest that the more infants engage in “conversational” turn-taking (even if it’s just with cooing and babbling) with their caregivers, the more likely they are to show advanced language skills later on. This has been taken to suggest that responsive interaction, rather than just passive exposure to language, plays a crucial role in language development. But as I note under the heading of ‘Child Directed Speech and Langage’, CDSL, or ‘Motherese’, this needs to be separated from the expression of bonding between mother and baby.

As babies approach the age of one, their babbling starts to become more ‘speech-like’, even before they begin speaking actual words.

The early “conversational” aspect of babbling where the baby babbles and the caregiver responds is sometimes thought to set the stage for conversation by language proper.