Architecture

Of the system

Talking and understanding are not just about words, but about the architecture of the different aspects of the grammar – the morphology, the syntax, the phonology, the semantics. Words are obviously composed of parts, place and -S or -D in places and placed, and Re- in replaces and replaced. But how do these fit together? In what order?

Do speakers have something they want to say and find the words to fit? Are forms extracted from the lexicon in the way they are spoken? Or are they built, bit by bit?

- Is the meaning conceived first, some desired intention, with the words strung together fully formed to express that intention?

- Or is the structure defined first, with the words fitted into the structure according to the intention?

- Or are the meanings separate from the structures and the intentions?

- Or is the building in parts, with various sub-assemblies?

All of these ideas have been entertained.

In extremis, this can be a matter of life and death. In a manual for aircraft maintenance, there was an instruction to replace a bolt in certain circumstances. An engineer understood this as ‘place it again’ instead of the intended ‘throw it away and find a new one’, with the meaning hinging on the meaning of RE and how it is pronounced in the spoken language. A worn bolt was put back rather than being replaced. A cockpit window blew out, and the pilot was half sucked out the aircraft, and only saved by the quick thinking and strength of a colleague who grabbed his legs and held onto them until the plane could be landed by the co-pilot.

How does the learning process work? How does it reach a predictable conclusion, what we call a ‘grammar‘, despite an infinite variety of input evidence, much of it not fully grammatical when adults fail to complete their sentences or accidentally make what they would recognise as grammatical mistakes if others made them. The learning process is not obvious at all. It is not even obvious whether to call it ‘learning’.

The first formulation of the questions here was by Chomsky (1965). He proposed a distinction between three criteria, what he called ‘observational adequacy’ – describing what happens in a language, ‘descriptive adequacy’ – describing both what does, and just as importantly, what does not happen, and ‘explanatory adequacy’ – doing this in such a way that it can be learnt by children in a given time frame (from birth to around the age of ten) from limited evidence varying from one child’s experience to the next child’s. And he proposed a dedicated ‘Language Acquisition Device’.

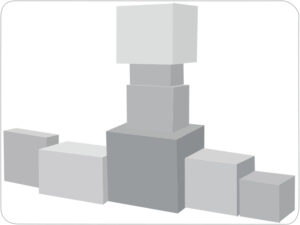

By the framework here and the proposal here, following some aspects of Chomsky’s current work, there is an architecture by which the meanings and intentions are built step by step, or in what are now generally known as ‘phases’. For example, in English “Who is doing what?” is a question and “He is seeing who?” is not a question but an expression of surprise. In the first, who is displaced from one point in the structure to another. In the second it stays put. The structural difference is an abstract element on the left edge which ‘attracts’ who leftwards, but only in the case of a true question.

For those (many) linguists who think that there are questions worth asking here, it may seem that the answer is in what is now known as the ‘architecture’ of language, the way the most essential parts are put together. In a way that may seem surprising, by the architectural framework here, neither the semantics nor the physical expression either spoken or signed are part of the main system. They just interface with the main system by successive instances of what is known as ‘Spell out’. The semantics has a structure of its own which has been the topic of intense on-going research and debate since the time of Plato and Aristotle.

The elements of this architecture, defining the core of what the language learner has to learn, are universal, but the ways they are brought into play are language-specific, and thus forcibly part of what Marlys Macken (1995) called the learnability space.